Why Size Isn’t Everything

Hedge fund survivor bias is especially insidious for the largest firms. Large hedge fund survivor bias overstates expected performance of the biggest firms by nearly half and their risk adjusted return from security selection (stock picking) by 80%. It is impossible to predict the largest funds of the future, but one doesn’t have to – robust skill analytics identify funds that will do even better in the future than tomorrow’s largest.

Past Performance of Today’s Largest Hedge Funds

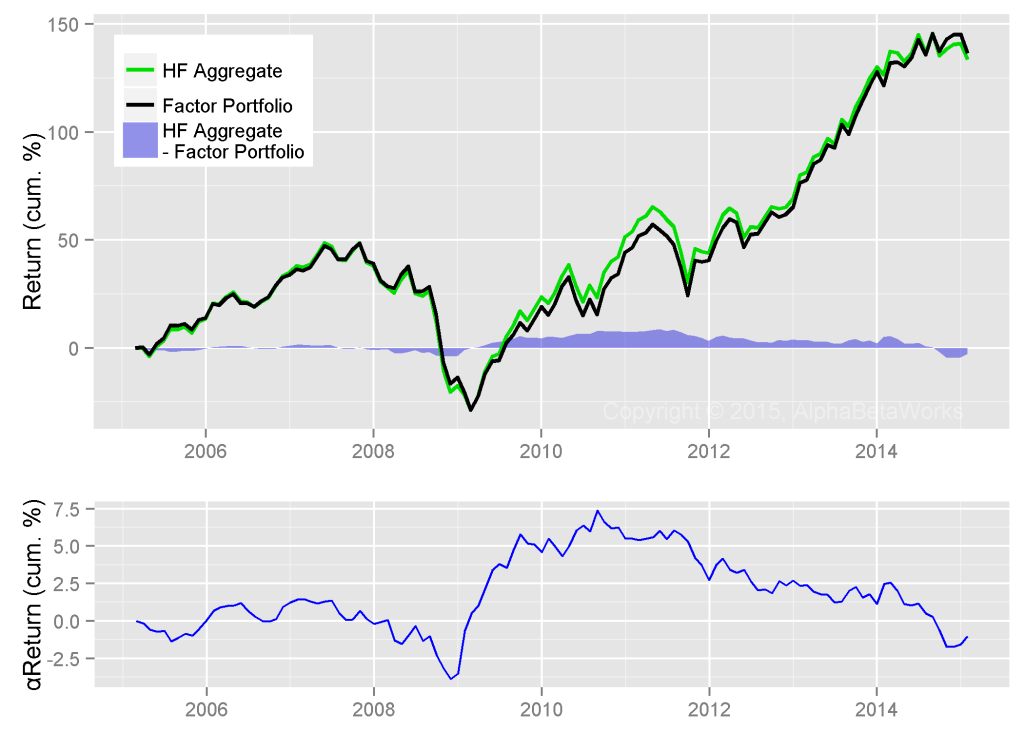

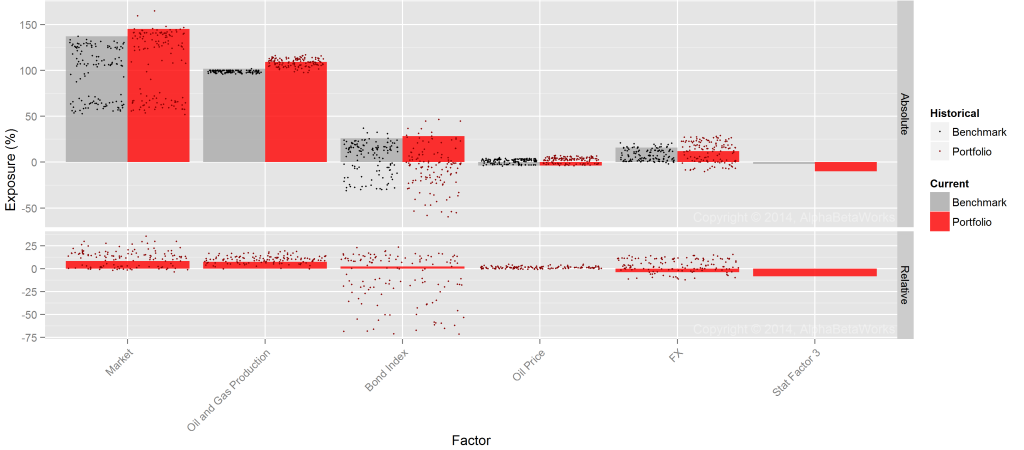

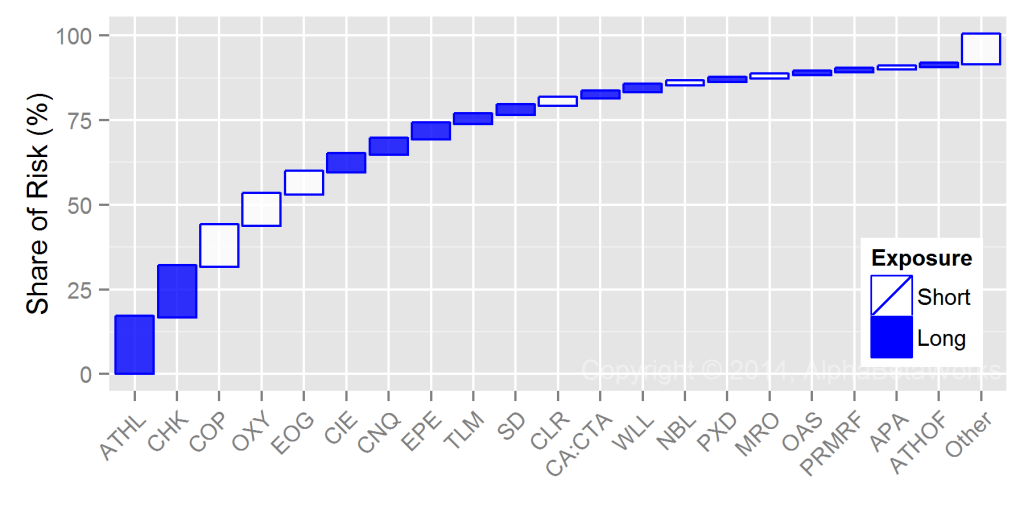

We follow the approach of our earlier piece on hedge fund survivor (survivorship) bias, which analyzed firms’ long U.S. equity portfolios (HF Aggregate). This dataset spans the long portfolios of all hedge funds active over the past 10 years that are tractable using 13F filings.

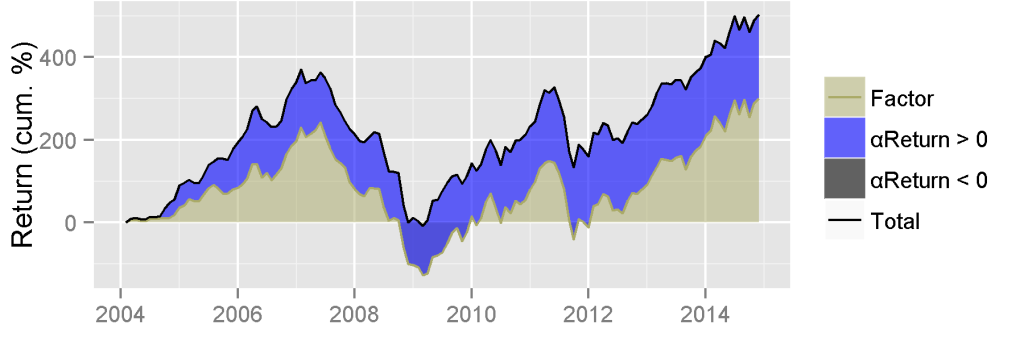

We compare group returns to Factor Portfolio – a portfolio with matching factor (systematic) risk. Factor Portfolio captures the return of investing passively in ETFs and index futures with the same risk as the group. This comparison reveals security selection (stock picking) performance, or αReturn – outperformance relative to the Factor Portfolio and the return that would have been generated if markets had been flat.

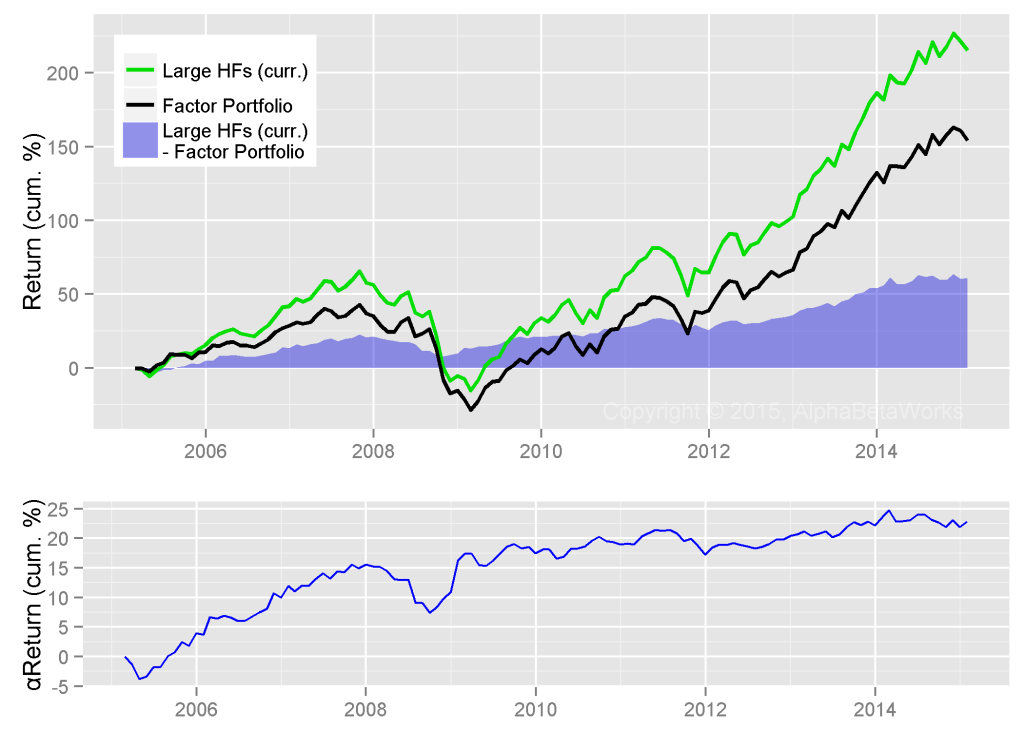

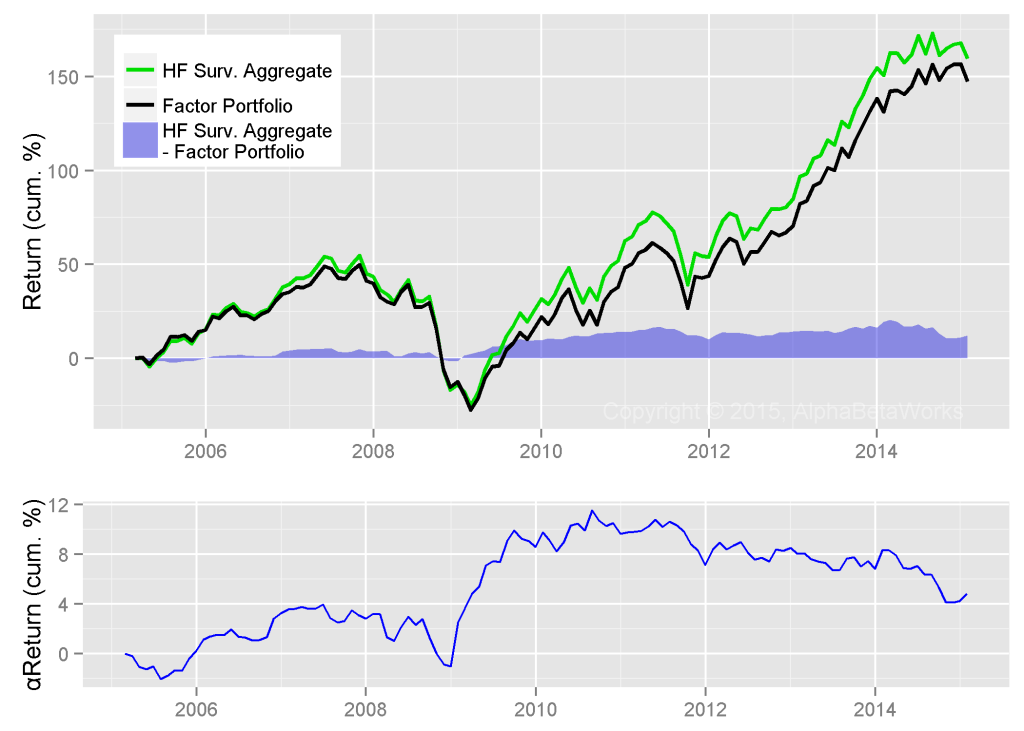

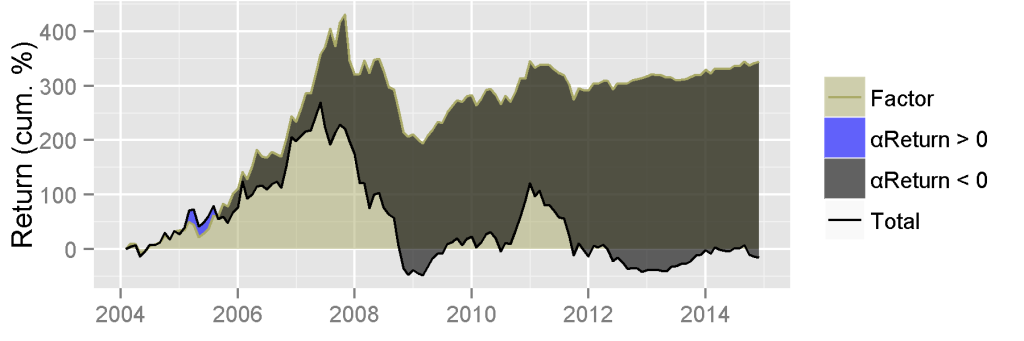

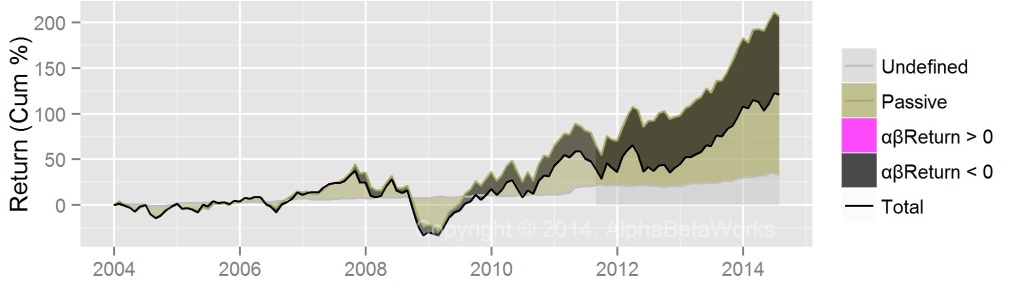

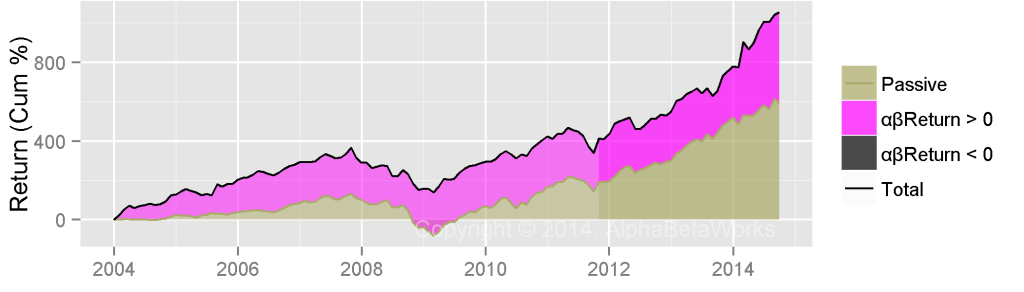

The following chart compares the performance of the 20 largest U.S. equity hedge fund long portfolios (Large HFs, green) to the Factor Portfolio (black). The security selection performance, or αReturn (blue), is the difference between the two. This is the average past performance of the 20 largest funds of 2015:

|

Returns (%) |

||

|

Annualized |

10-year Cum. |

|

| Total |

11.48 |

215.26 |

| Factor |

9.33 |

154.29 |

| Total – Factor |

2.15 |

60.97 |

Firms that have grown the largest over the past 10 years have performed exceptionally well: Including the effect of compounding, their long portfolios generated 61% higher return than their passive equivalents. If markets had been flat for the past 10 years, their long equity portfolios would have appreciated by nearly 25%.

The allure of this past performance arouses fund-following, guru-tracking, and billionaire portfolio strategies. But there is one problem: Today’s largest funds represent a top-performing sliver of the thousands of funds active in the past. Of the thousands of funds, some truly are skilled, but many simply got lucky on aggressive bets and became large as a result, irrespective of their skill. This constitutes large hedge fund survivor bias. This performance does not persist and tends to mean-revert.

Future Performance of Yesterday’s Largest Hedge Funds

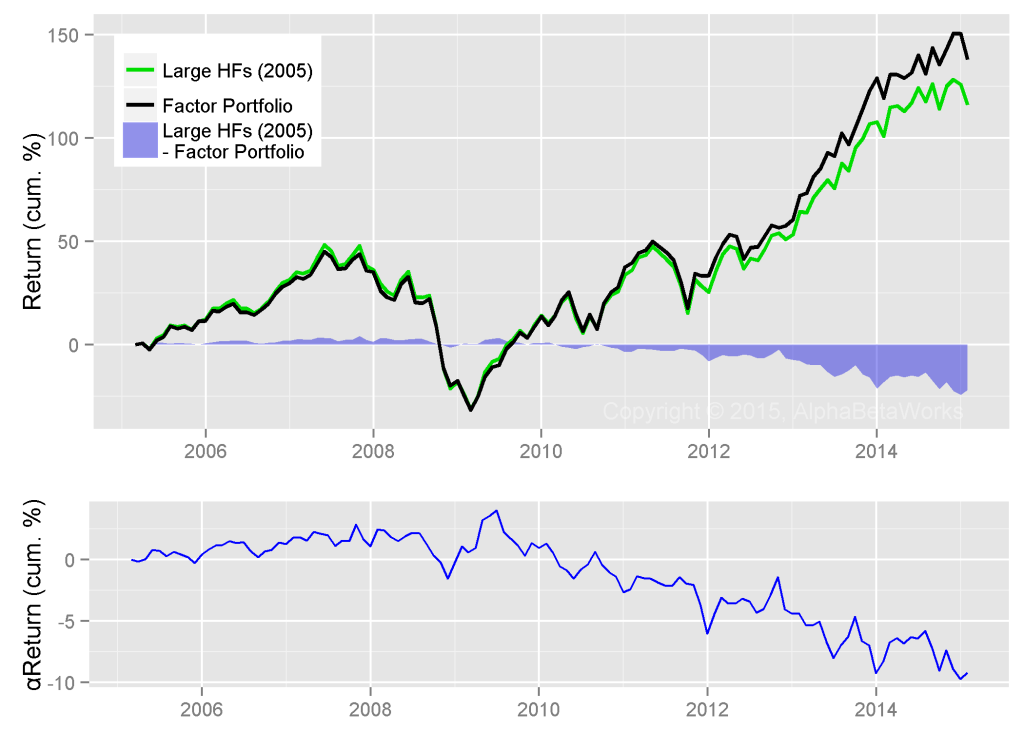

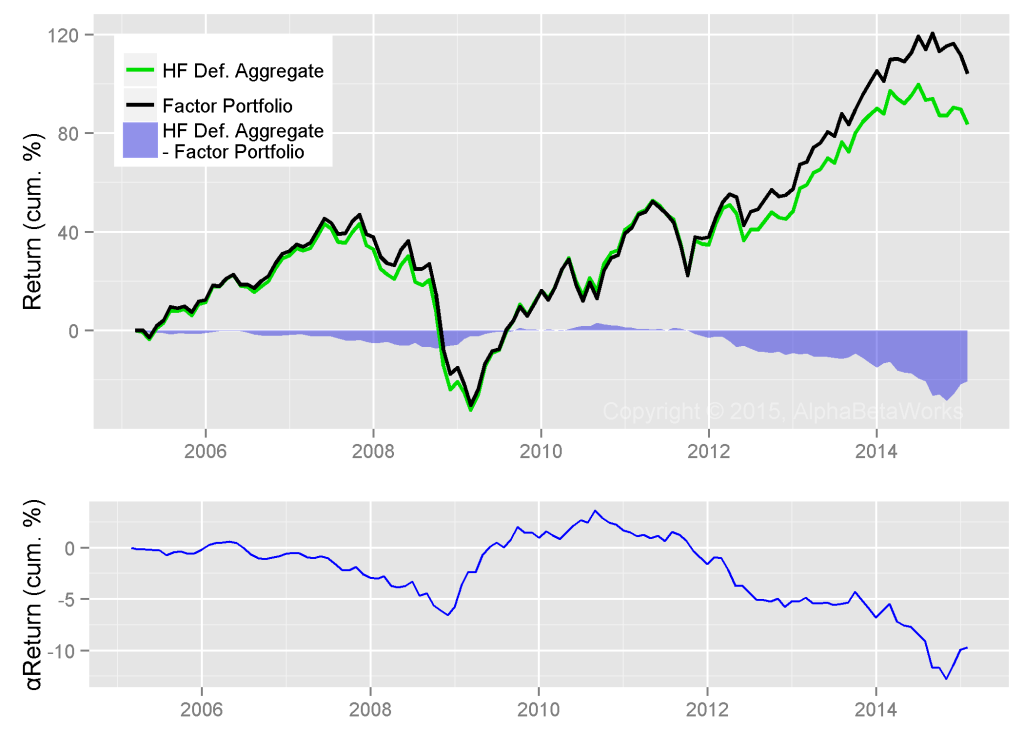

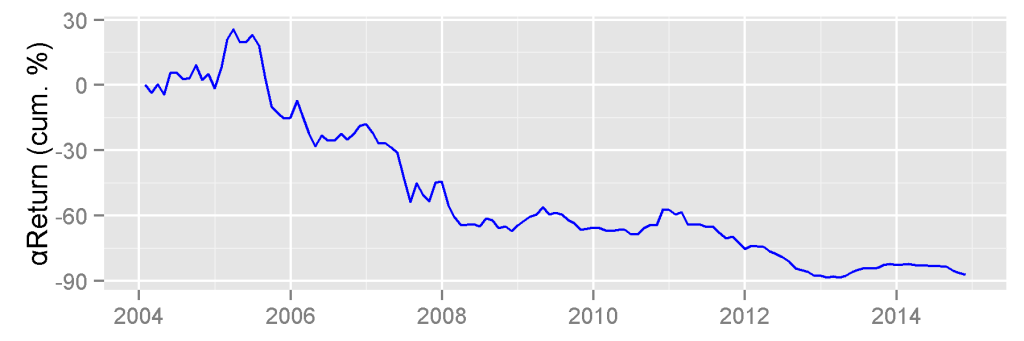

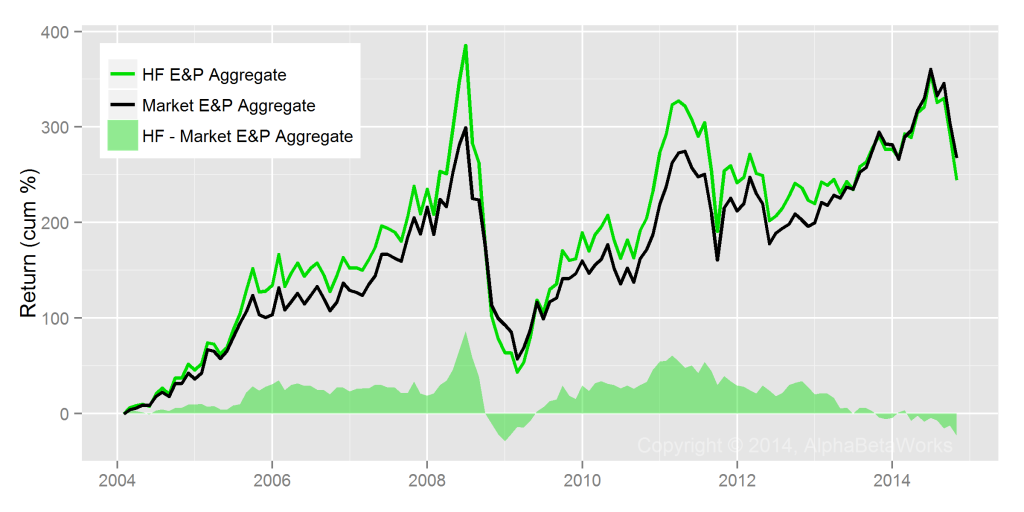

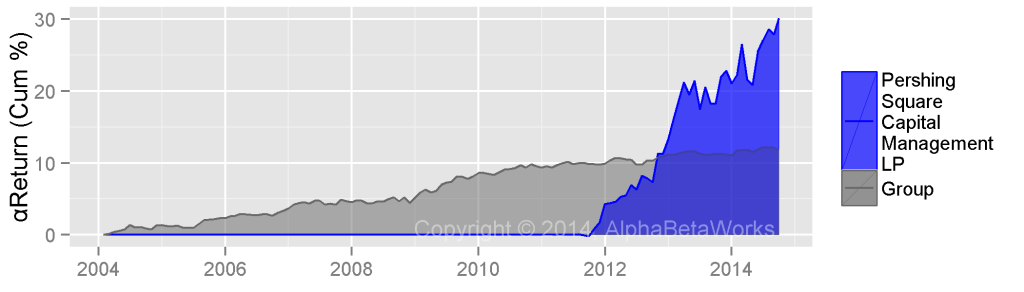

Most billionaire and guru-following strategies make the assumption that the largest funds are likely to continue generating strong returns. To test this, we tracked the 20 largest long U.S. equity hedge fund portfolios of 2005. Below is the unappealing picture of their average performance:

|

Returns (%) |

||

|

Annualized |

10-year Cum. |

|

| Total |

7.70 |

116.05 |

| Factor |

8.68 |

138.11 |

| Total – Factor |

-0.97 |

-22.05 |

The 2005 Large HF Aggregate tracked Factor Portfolio closely until 2010 and has struggled since. Hence, including the effects of compounding, large hedge fund survivor bias overstated security selection returns by 80%.

Size does not always signal quality, nor does it guarantee future performance. Between 2005 and 2015, the forward-looking performance of the largest long hedge fund portfolios of 2005 was just over half the backward-looking performance of 2015’s largest. Why then would the largest hedge funds of 2015 perform differently than the poor showing of the 2005 vintage?

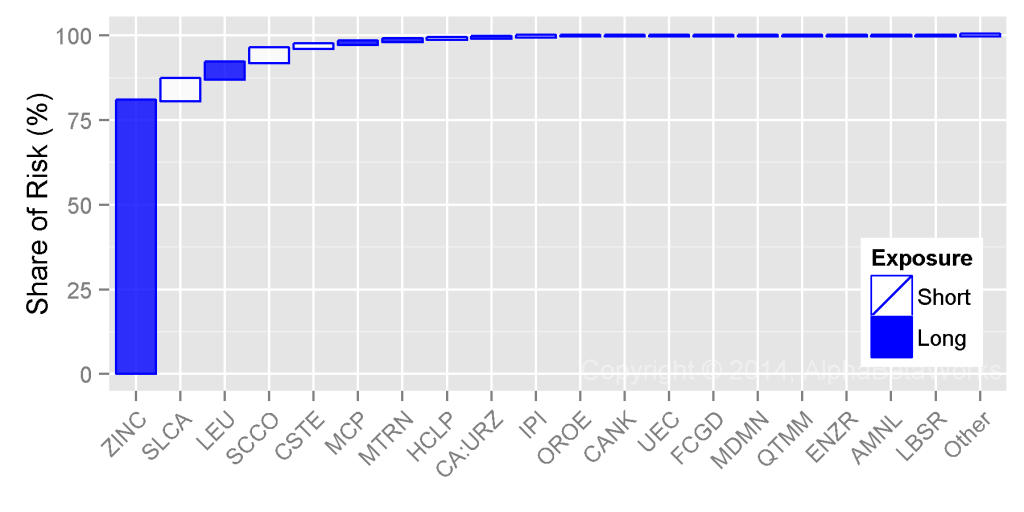

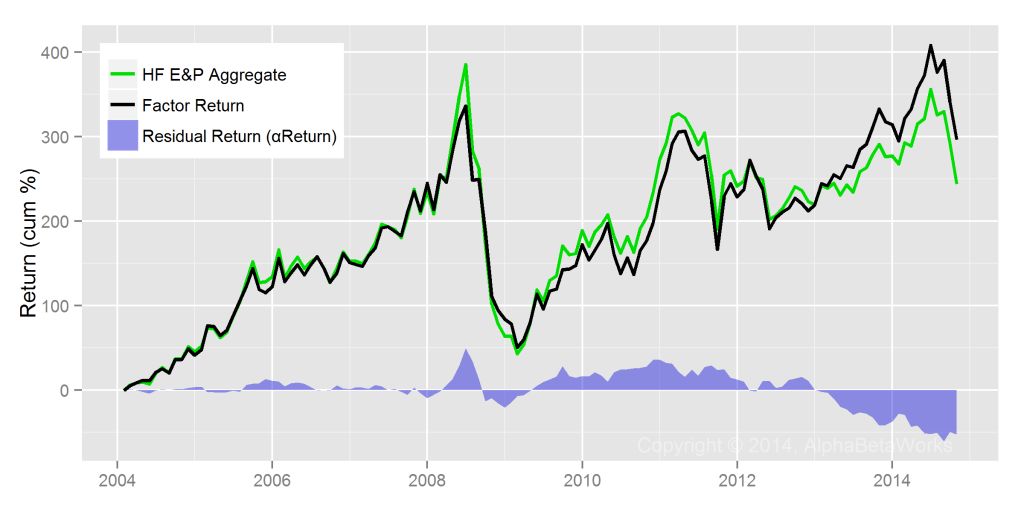

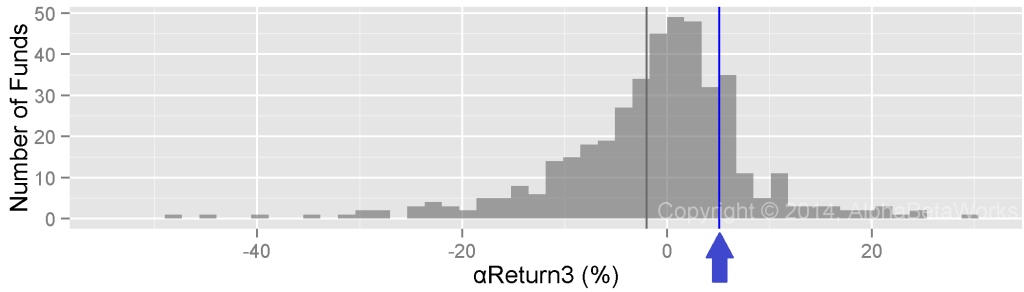

Predicting Top Future Hedge Funds: Stock Picking Skill

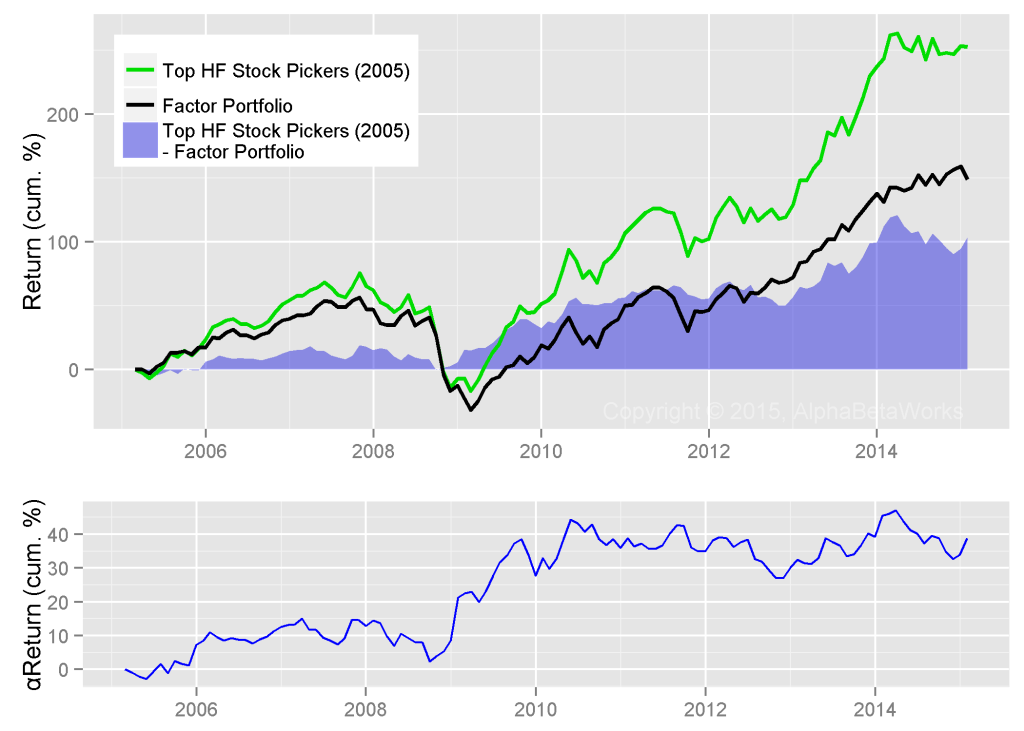

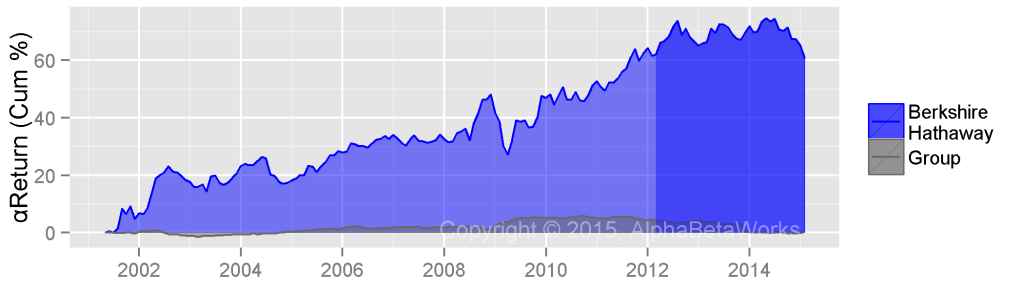

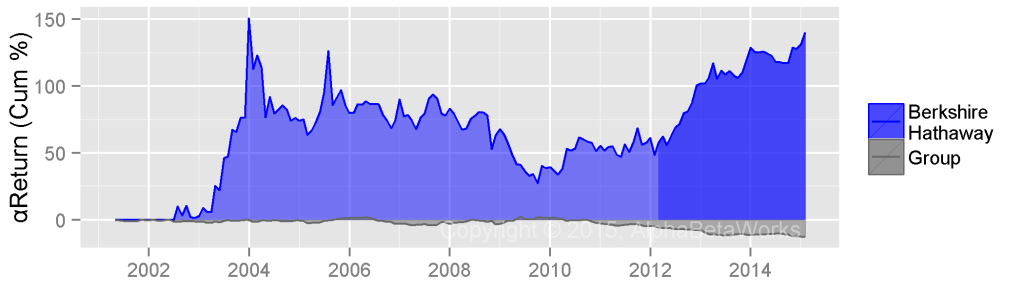

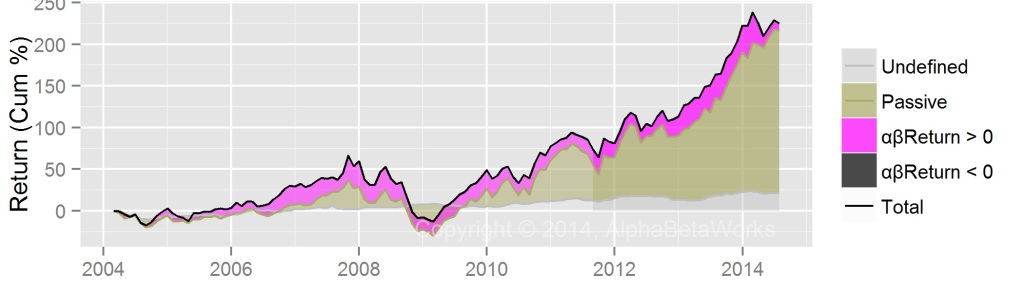

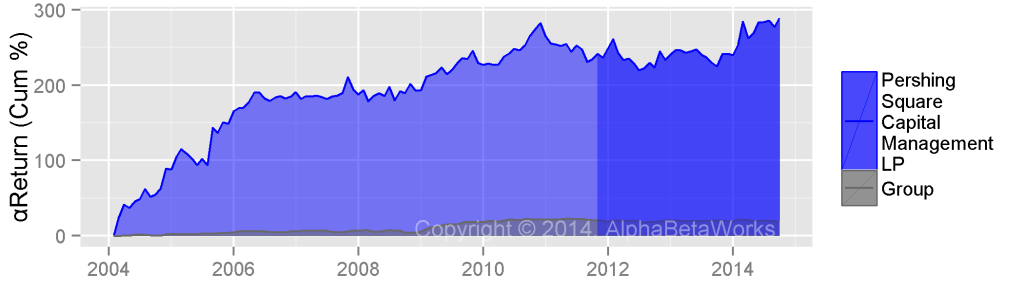

Absent a time machine, investors cannot know who will be the future stars. However, they need not despair. Instead of focusing on the largest or top-performing funds of the past, they can turn to those showing the highest evidence of skill. The following chart tracks the long U.S. equity portfolios of 20 hedge funds with the highest 3-year αReturn as of 12/31/2005:

|

Returns (%) |

||

|

Annualized |

10-year Cum. |

|

| Total |

12.60 |

252.58 |

| Factor |

9.11 |

148.70 |

| Total – Factor |

3.49 |

103.88 |

The funds above were the best stock pickers of 2005, not the largest. If markets had been flat for the past 10 years, the top stock pickers of 2005 would have returned 40%. For a variety of reasons (scalability constraints, lifestyle preferences), many have not become the largest or best known, but their risk-adjusted returns are strong.

Since active management skills persist, skilled stock pickers of the past continue to generate strong nominal and risk-adjusted returns. The same analysis identifies today’s top stock pickers who will be tomorrow’s outperformers – and without the cost of a time machine!

Conclusions

- Hedge fund survivor bias is larger for the largest hedge funds.

- Between 2005 and 2015, large hedge fund survivor bias overstated expected nominal performance by nearly 100% and security selection performance by 80%.

- Chasing large hedge funds is unnecessary and detrimental. Selecting a fund using robust skill analytics, as illustrated by αReturn, is superior to flawed results hampered by large hedge fund survivor bias.