There is a large difference between momentum strategies in theory and in practice. Given that much of its model performance derives from illiquid securities and high turnover, the academic momentum factor is a theoretical ideal that is not directly investable. Consequently, real-world momentum products, such as momentum ETFs, are restricted to investable liquid securities and usually reduce the approximately 200% annual turnover of theoretical momentum portfolios. After these modifications, their idiosyncratic momentum returns mostly vanish.

We consider a popular momentum ETF and illustrate that its historical performance is almost entirely attributable to passive exposures to simple non-momentum factors, such as Market and Sectors. Investors may thus be able to achieve and even surpass the performance of popular momentum ETFs with transparent, passive, and potentially lower-cost portfolios of simpler funds.

Attributing the Performance of Momentum ETFs to Simpler Factors

We analyzed iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor ETF (MTUM) using the AlphaBetaWorks Statistical Equity Risk Model – a proven tool for forecasting portfolio risk and performance. We estimated monthly positions from regulatory filings, retrieved positions’ factor (systematic) exposures, and aggregated these. This produced a series of monthly portfolio exposures to simple investable risk factors such as Market, Sector, and Size. The factor exposures at the end of Month 1 and factor returns during Month 2 are used to calculate factor returns during Month 2 and any residual (security-selection, idiosyncratic, stock-specific) returns un-attributable to factors.

There are only two ways for a fund to deviate from a passive portfolio: residual returns un-attributable to factors and factor timing returns due to variation in factor exposures over time. We define and measure both components below.

iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM): Performance Attribution

We used iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM) as an example of a practical implementation of a theoretical momentum portfolio. MTUM is a $1.1bil ETF that seeks to track an index of U.S. large- and mid-cap stocks with high momentum. The fund’s turnover, around 100% annually, is about half that of the theoretical momentum factor.

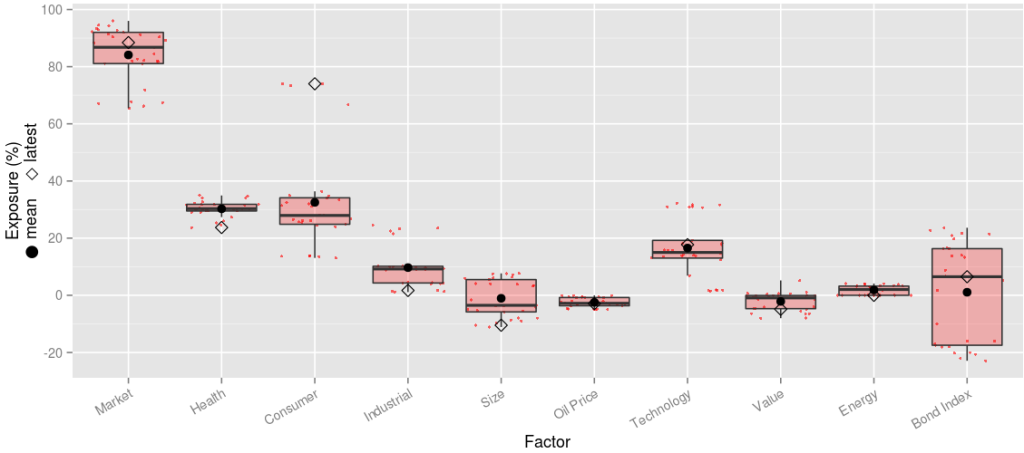

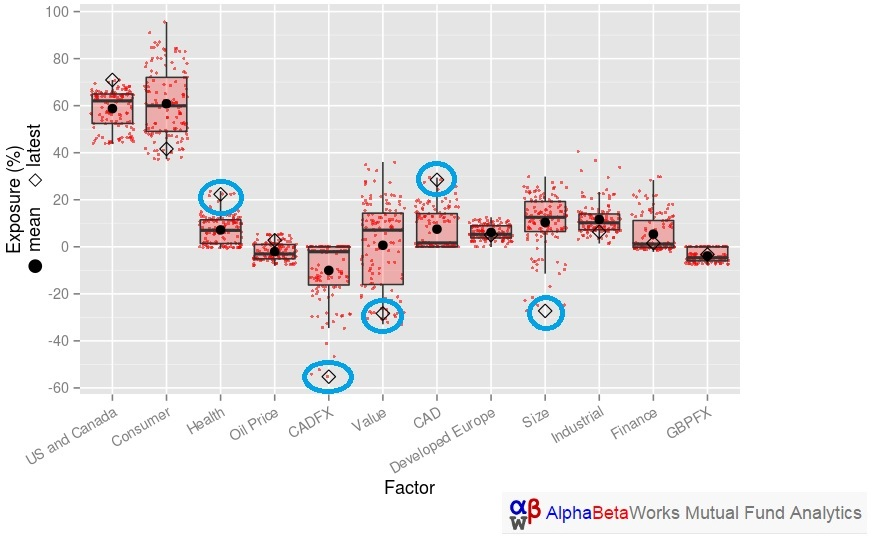

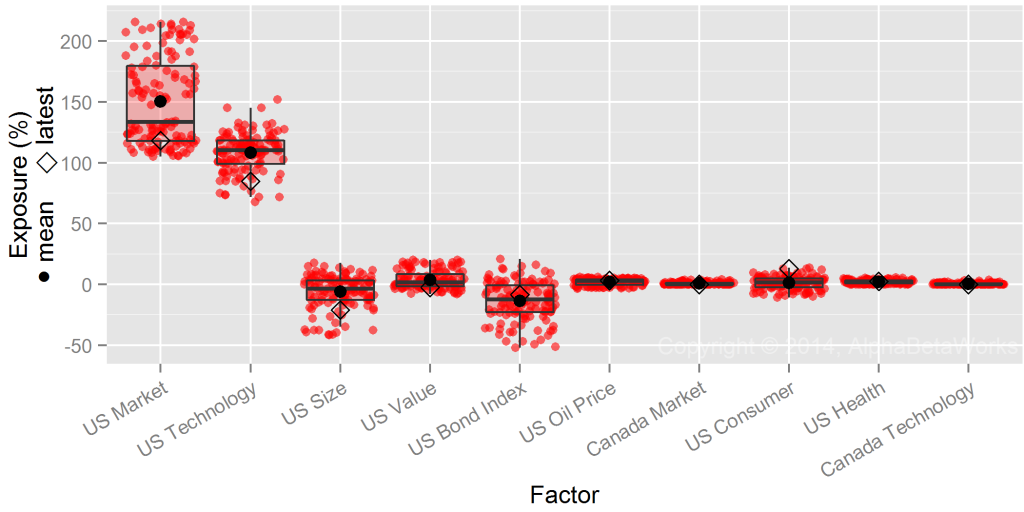

iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM): Factor Exposures

The following factors are responsible for most of the historical returns and variance of MTUM:

| Latest | Mean | Min. | Max. | |

| Market | 88.44 | 84.12 | 65.46 | 96.03 |

| Health | 23.73 | 30.28 | 23.73 | 34.94 |

| Consumer | 74.02 | 32.53 | 13.10 | 74.06 |

| Industrial | 1.69 | 9.71 | 1.13 | 24.51 |

| Size | -10.47 | -1.04 | -11.09 | 7.67 |

| Oil Price | -2.90 | -2.45 | -4.94 | -0.04 |

| Technology | 17.72 | 16.56 | 1.50 | 32.29 |

| Value | -4.86 | -2.13 | -8.00 | 5.20 |

| Energy | 0.00 | 1.86 | 0.00 | 4.12 |

| Bond Index | 6.51 | 1.08 | -22.90 | 23.64 |

iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM): Active Return

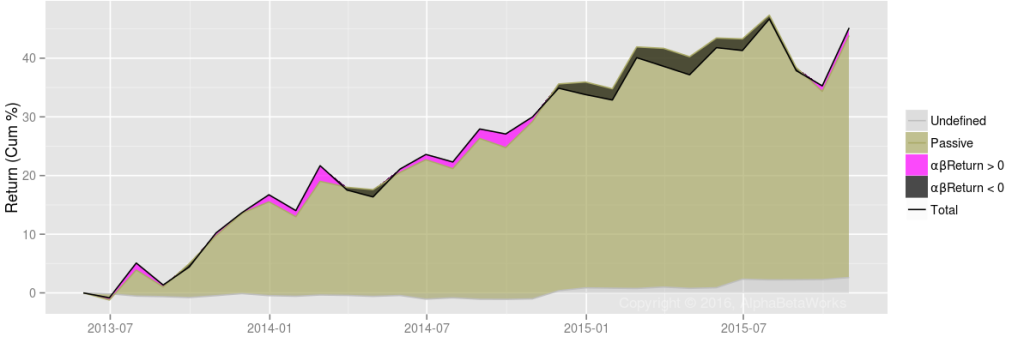

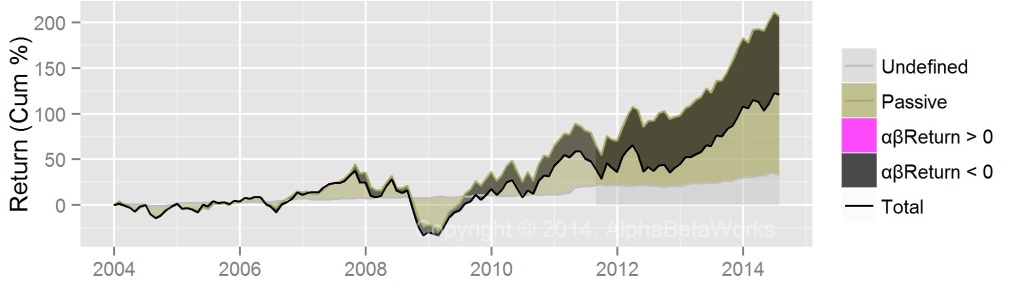

To replicate MTUM with simple non-momentum factors, one can use a passive portfolio of these simple non-momentum factors with MTUM’s mean exposures as weights. This portfolio defined the Passive Return in the following chart. Active return, or αβReturn, is the performance in excess of this passive replicating portfolio. It is the active return due to residual stock performance and factor timing:

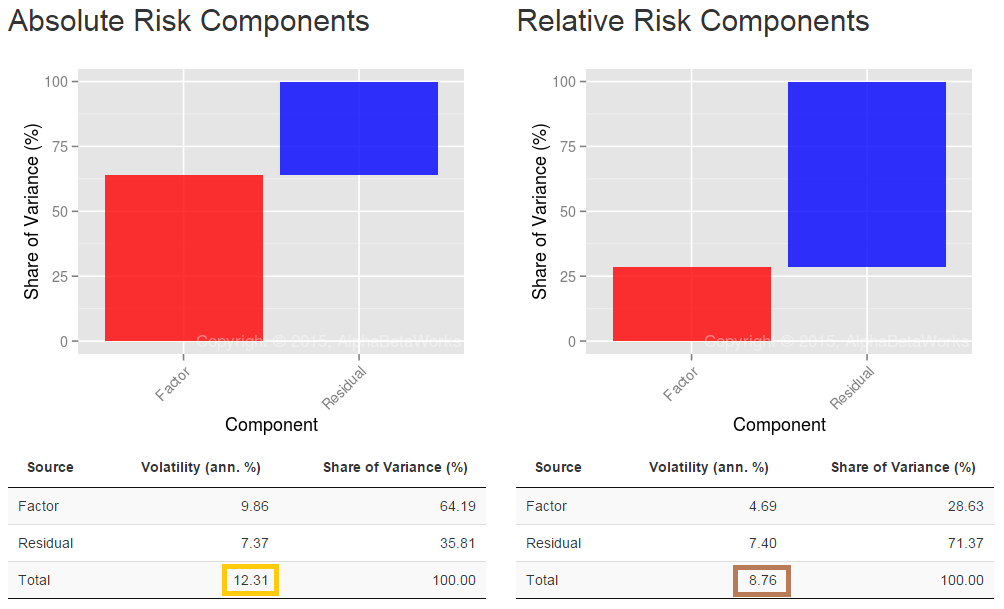

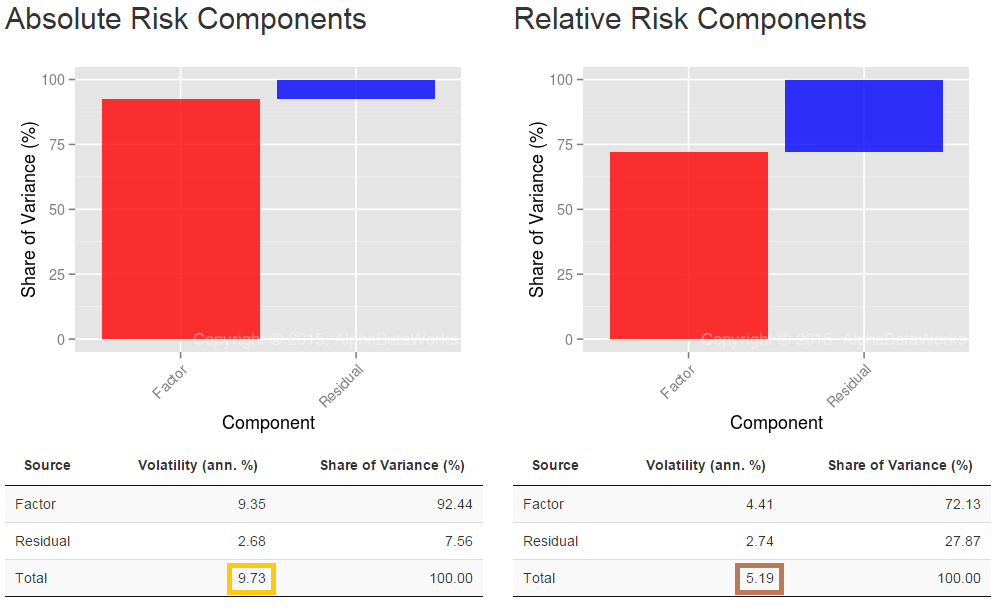

MTUM’s performance closely tracks the passive replicating portfolio. Pearson’s correlation between Total Return and Passive Return is 0.96. Consequently, 93% of the variance of monthly returns is attributable to passive factor exposures, primarily to Market and Sector factors.

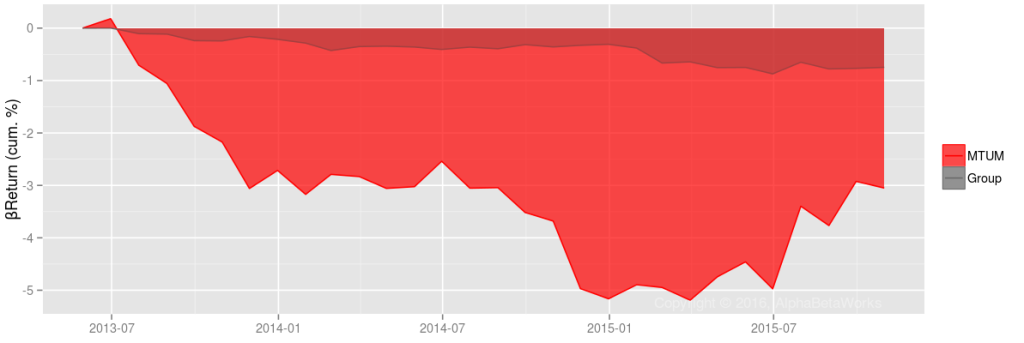

Once passive exposures to simpler factors have been removed, MTUM’s active return is negligible. Since MTUM’s launch, the cumulative return difference from such passive replicating portfolio has been approximately 1%:

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

| Total Return | 16.73 | 14.62 | 8.50 | 45.18 |

| Passive Return | 16.06 | 16.48 | 4.55 | 41.34 |

| αβReturn | 1.11 | -2.46 | 2.54 | 1.12 |

| αReturn | 3.91 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 4.27 |

| βReturn | -2.71 | -2.52 | 2.23 | -3.05 |

This active return can be further decomposed into security selection (αReturn) and factor timing (βReturn). These active return components generated low volatility, around 1% annually, mostly offsetting each other as illustrated below:

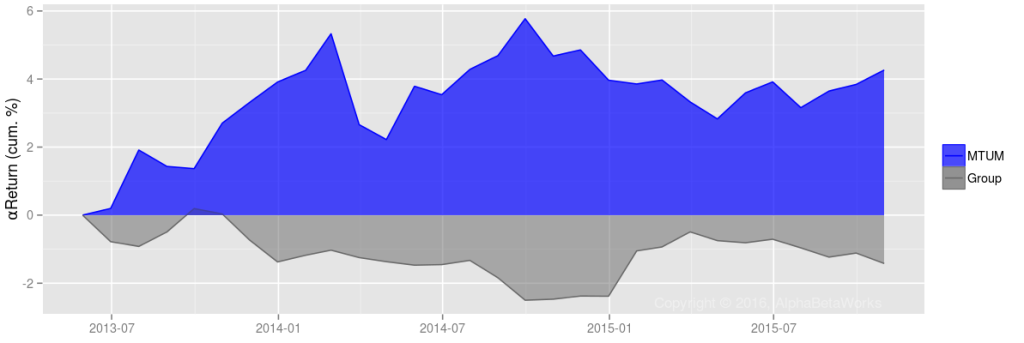

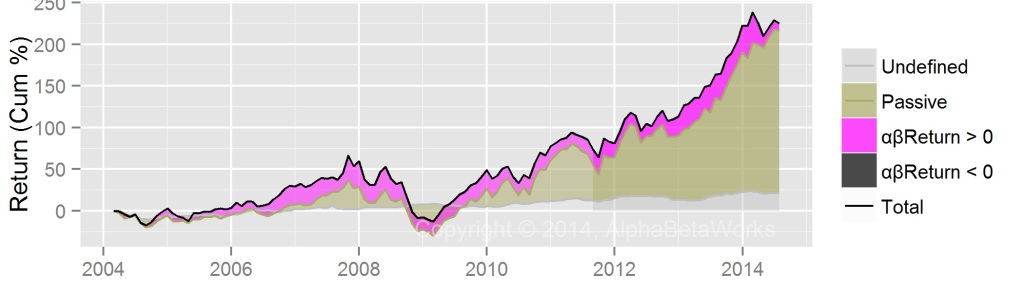

iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM): Active Return from Security Selection

AlphaBetaWorks’ measure of residual security selection performance is αReturn – performance relative to a factor portfolio that matches the funds’ historical factor exposures. αReturn is the return a fund would have generated if markets had been flat. MTUM has generated approximately 4% cumulative αReturn, primarily in 2013, compared to roughly 1.5% decline for the average U.S. equity ETF:

iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM): Active Return from Factor Timing

AlphaBetaWorks’ measure of factor timing performance is βReturn – performance due to variation in factor exposures. βReturn is the fund’s outperformance relative to a portfolio with the same mean, but constant, factor exposures as the fund. MTUM generates approximately -3% cumulative βReturn, compared to a roughly 1% decline for the average U.S. equity ETF:

These low active returns are consistent with our earlier findings that many “smart beta” funds are merely high-beta and offer no value over portfolios of conventional dumb-beta funds. It is thus vital to test any new resident of the Factor Zoo to determine whether they are merely exotic breeds of its more boring residents.

Conclusion

- Theoretical, or academic, momentum portfolios are not directly investable.

- A popular momentum ETF, MSCI USA Momentum Factor (MTUM), did not deviate significantly from a passive portfolio of simpler non-momentum factors.

- Investors may be able to achieve and surpass the performance of the popular momentum ETFs with transparent, passive, and potentially lower-cost portfolios of simpler index funds and ETFs.