Fund crowding consists of investment bets shared by groups of funds – large pools of capital chasing similar strategies. Within the hedge fund industry, long equity portfolios crowd into several clusters with similar systematic (factor) and idiosyncratic (residual) bets. This hedge fund clustering is the internal structure of hedge fund crowding.

This piece illustrates the large-scale hedge fund clustering and examines the largest hedge fund cluster in which:

- Factor crowding is due to two factors;

- Residual crowding is moderate and four stock-specific bets stand out.

Allocators who are unaware of hedge fund clustering and hedge fund crowding may be invested in an undifferentiated portfolio, paying active fees for passive factor exposure.

Hedge Fund Crowding and Hedge Fund Clustering

Several of our earlier articles on hedge fund crowding analyzed the factor (systematic) and residual (idiosyncratic) bets of HF Aggregate, which consists of the popular equity holdings of all long U.S. hedge fund portfolios tractable from regulatory filings.

Analysis of overall industry crowding does not address bets shared by fund groups within the aggregate. To explore this internal structure of hedge fun crowding – clusters of funds with shared systematic (factor) and idiosyncratic (residual) bets – in 2014 we released pioneering research on hedge fund clustering. The 2014 work proved predictive and invaluable to allocators. This piece updates the analysis of hedge fund clustering with Q2 2015 holdings data.

Hedge Fund Clusters

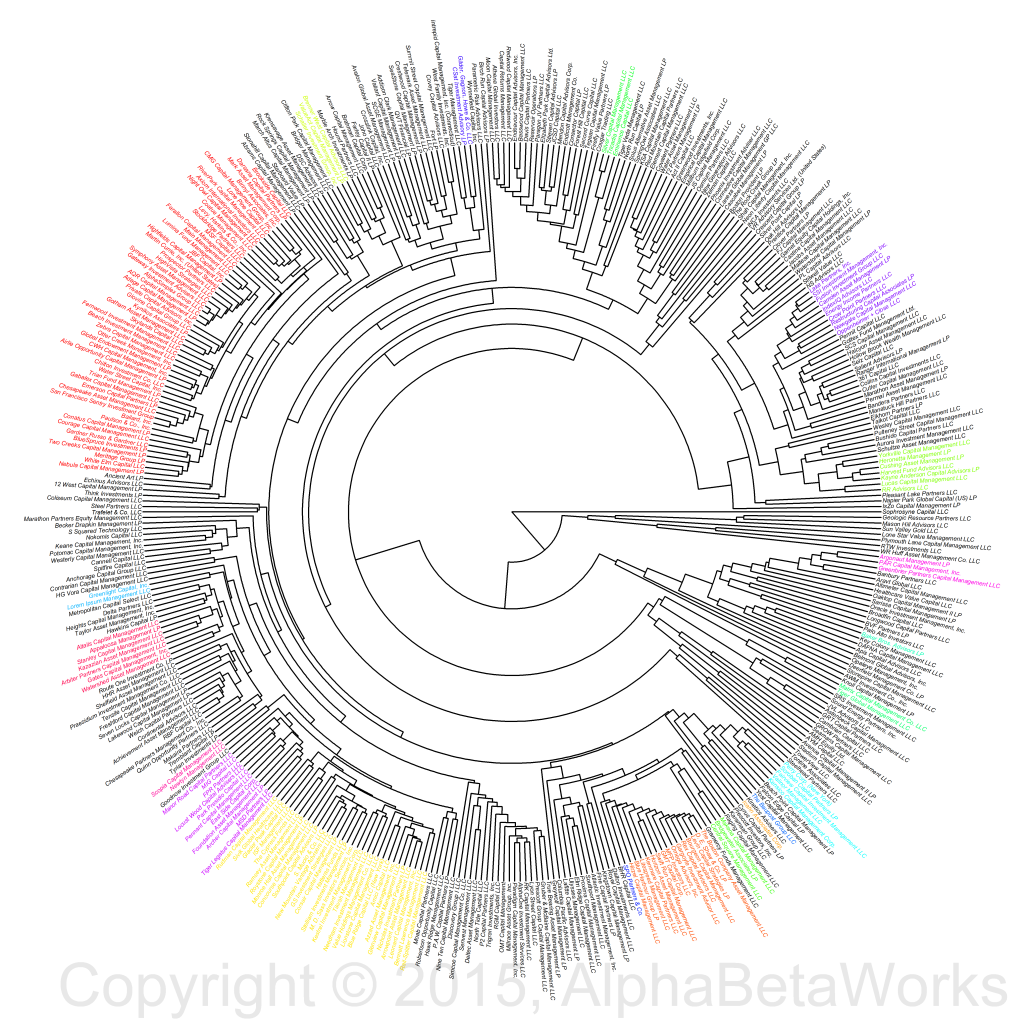

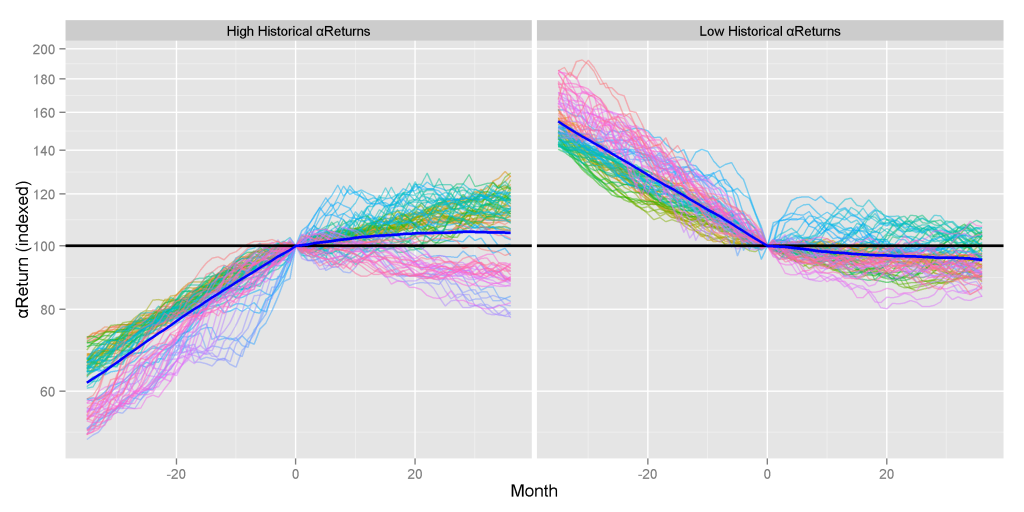

To explore hedge fund clustering we analyze long portfolios of every pair of hedge funds analyzable using regulatory filings using the AlphaBetaWorks’ Statistical Equity Risk Model, a proven tool for forecasting portfolio risk and future performance. For each portfolio pair we estimate the future relative volatility (tracking error). The lower the expected relative tracking error between two funds, the more similar they are to each other.

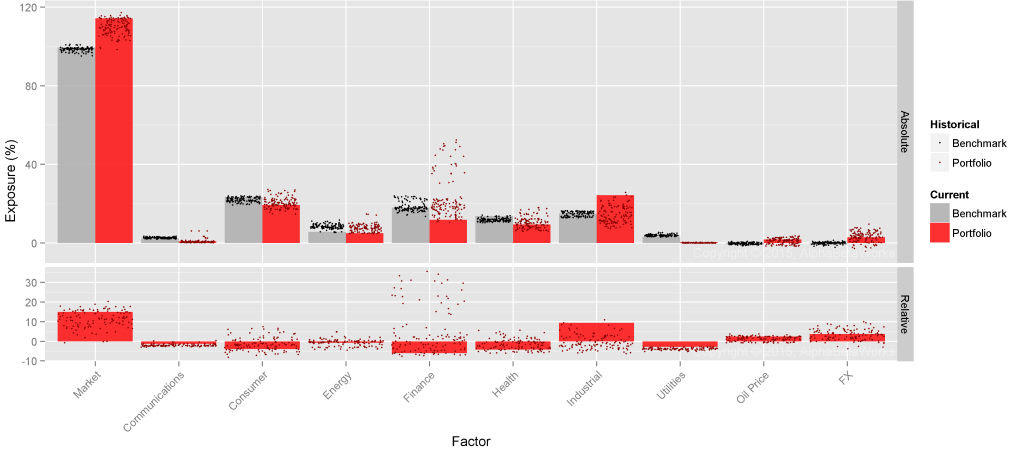

Once each hedge fund pair is analyzed – hundreds of thousands of factor-based risk analyses – we identify groups of funds with similar factor and residual exposures and build clusters (similar to phylogenic trees, or family trees) of the funds’ long portfolios. We use agglomerative hierarchical clustering with estimated future relative tracking error as the metric of differentiation or dissimilarity. The result is a picture of clustering among all analyzable U.S. hedge funds’ long portfolios:

The largest cluster contains approximately 50 funds. A number of portfolios had exposures that were so similar, we expect their relative annual volatility to be under 3% – their annual returns should differ from one another by less than 3% about two thirds of the time.

This is critical for allocators: if they are invested in clustered funds, they may be paying high active fees for a handful of passive factor bets and consensus stock picks.

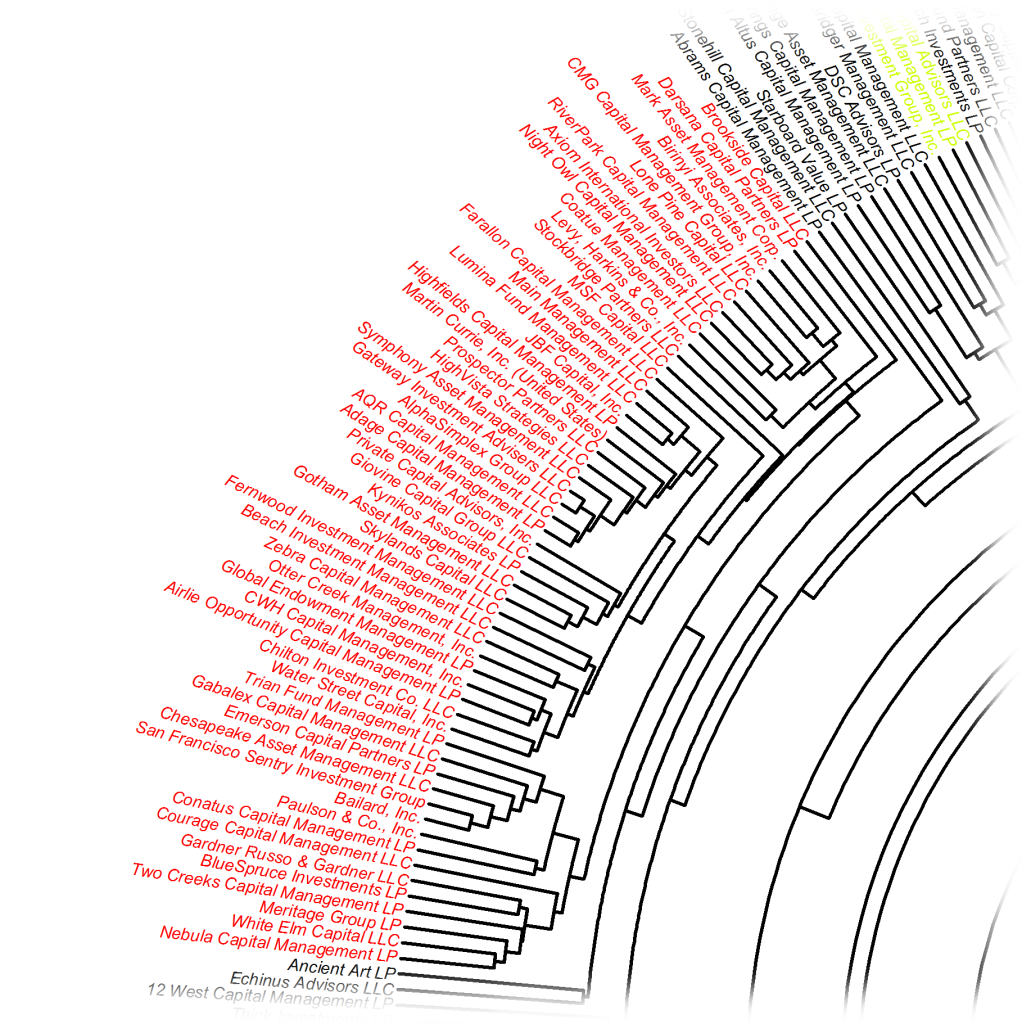

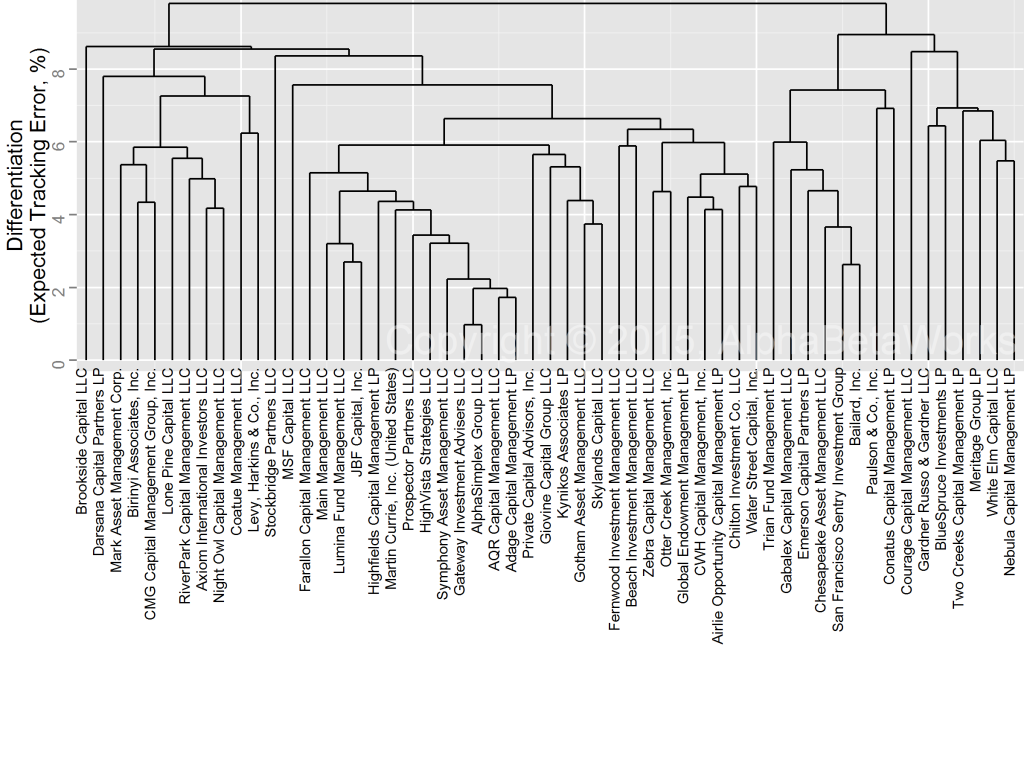

The AQR-Adage Hedge Fund Cluster

The largest cluster is currently the AQR-Adage Cluster, named after two of its large members with similar long exposures:

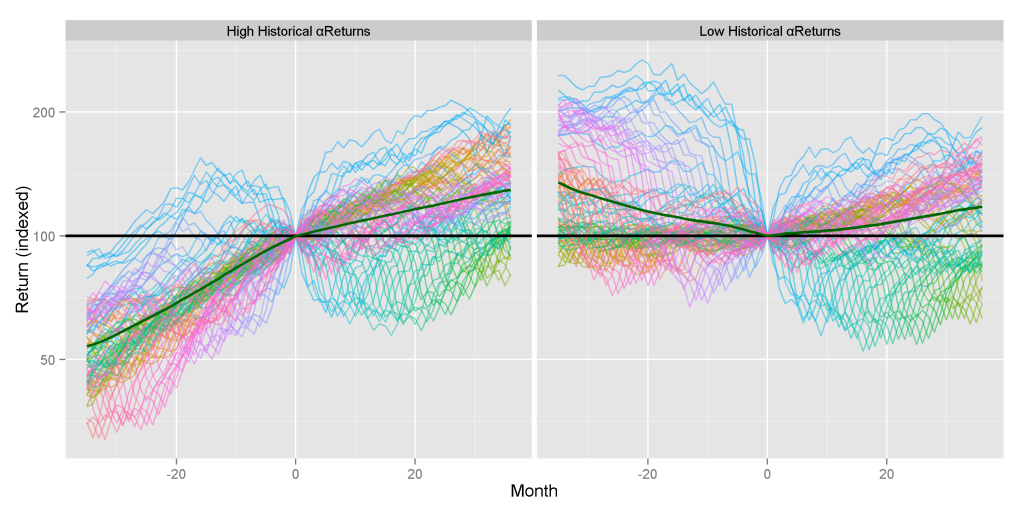

A flat diagram of the cluster better illustrates the distances (estimated future tracking errors) between its members:

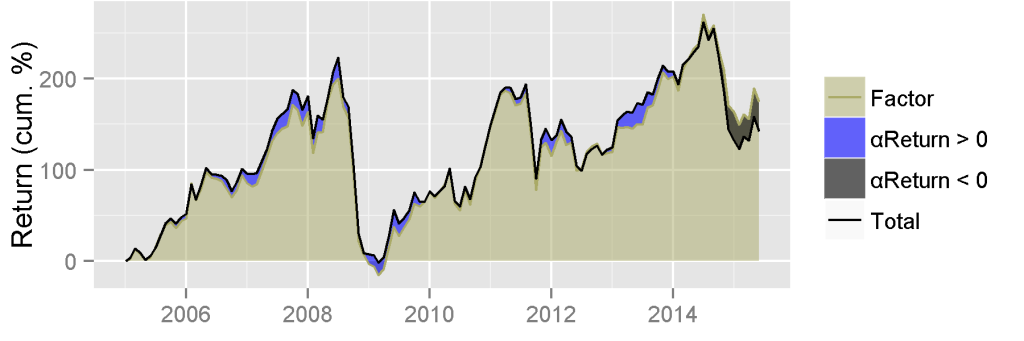

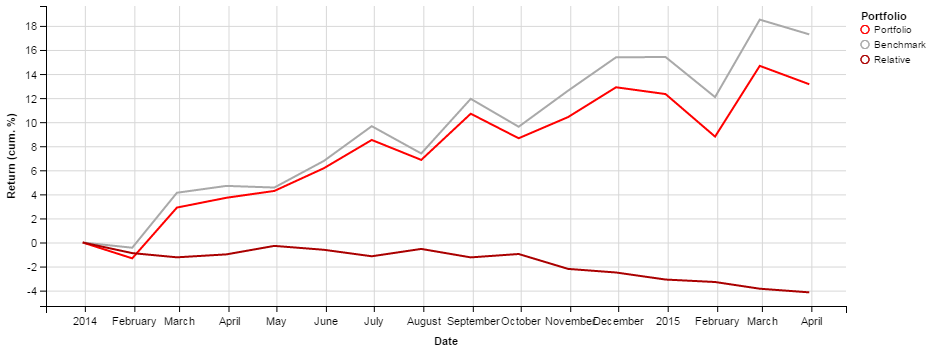

In aggregate, this cluster’s risk is very close to that of the U.S. equity market. We estimate the AQR-Adage Cluster’s expected tracking error relative to the Russell 3000 Index at 1.4%.

| Source |

Volatility (%) |

Share of Variance (%) |

| Factor |

0.97 |

48.18 |

| Residual |

1.01 |

51.82 |

| Total |

1.40 |

100.00 |

Put differently, we expect this cluster’s aggregate long portfolio return to differ from the market by more than 1.4% only about a third of the time.

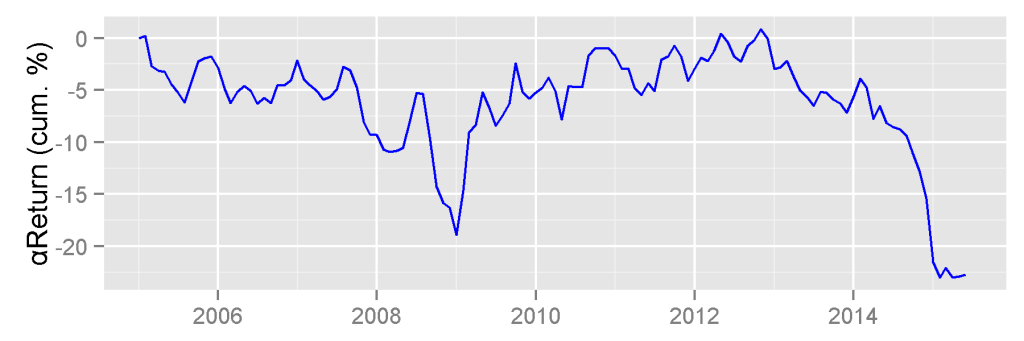

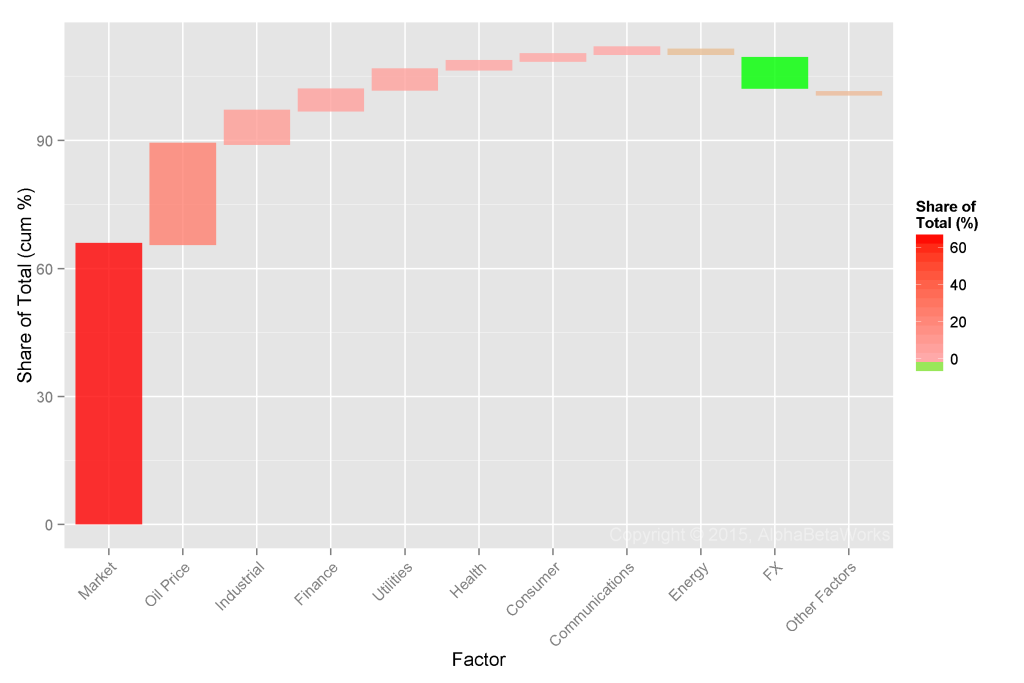

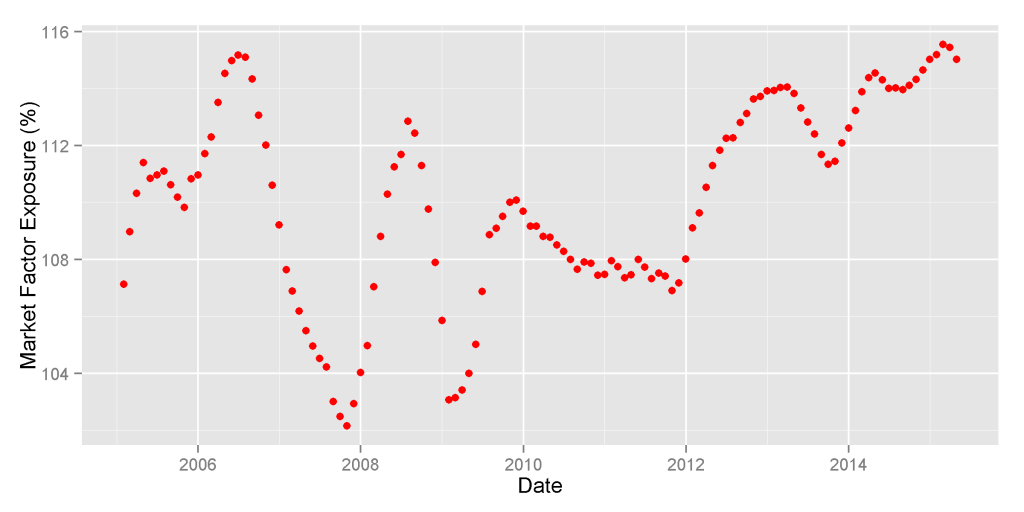

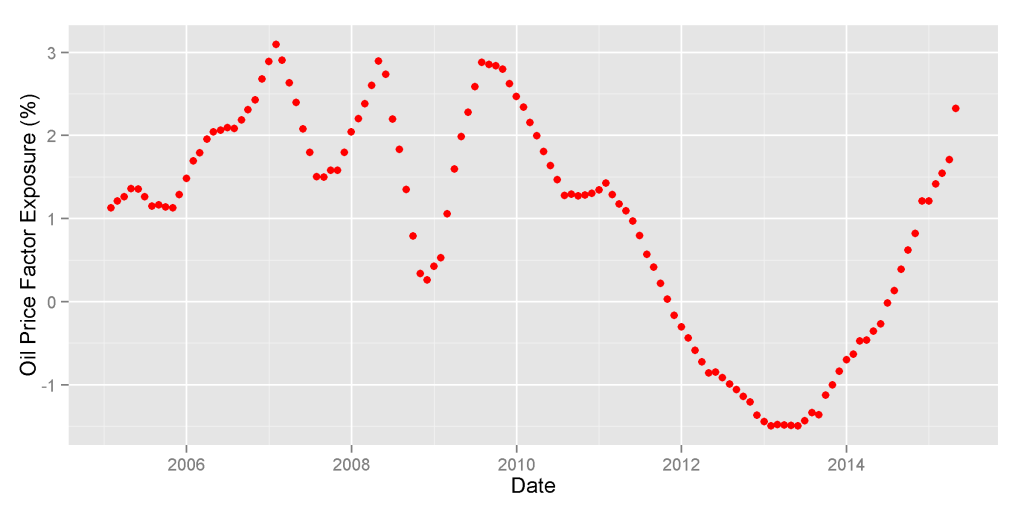

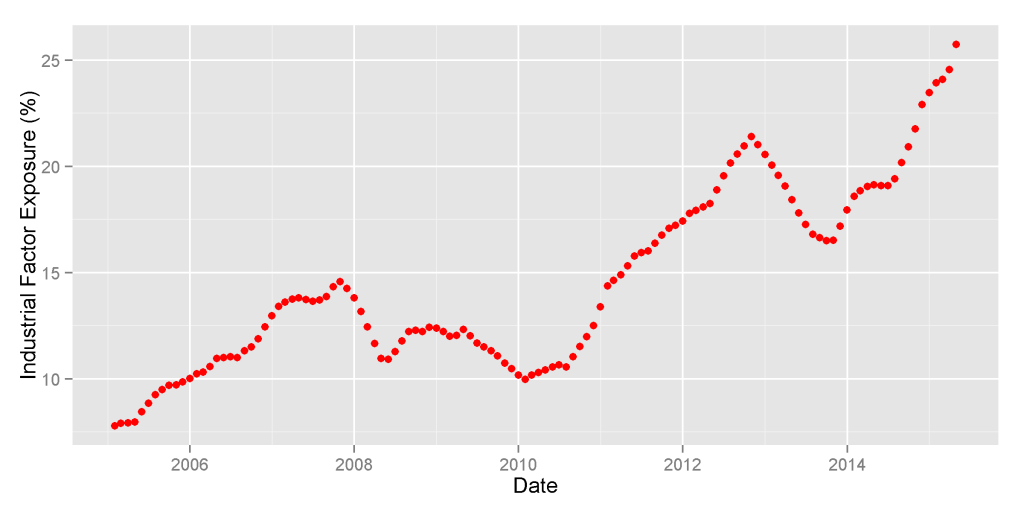

AQR-Adage Cluster Factor (Systematic) Crowding

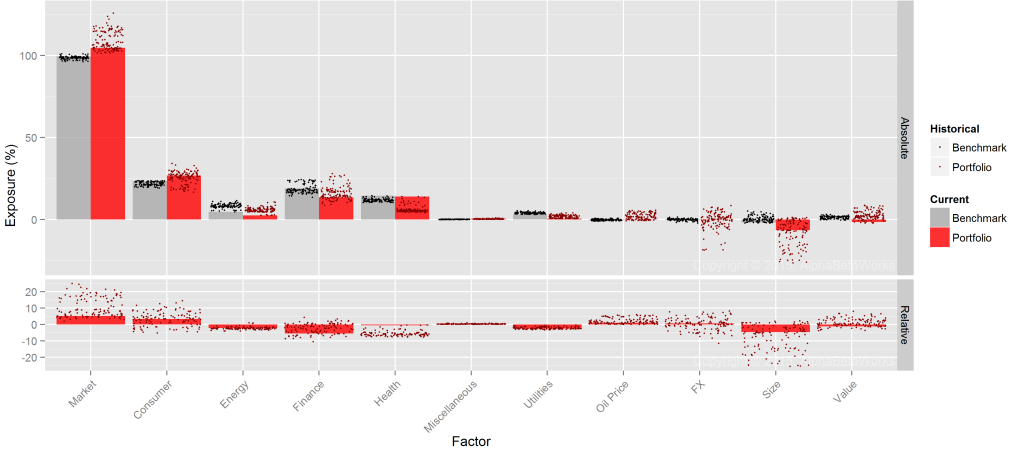

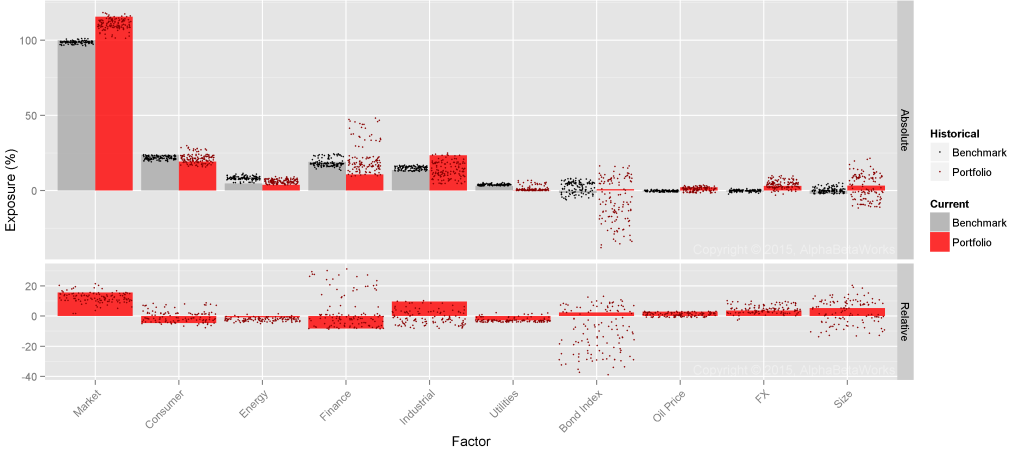

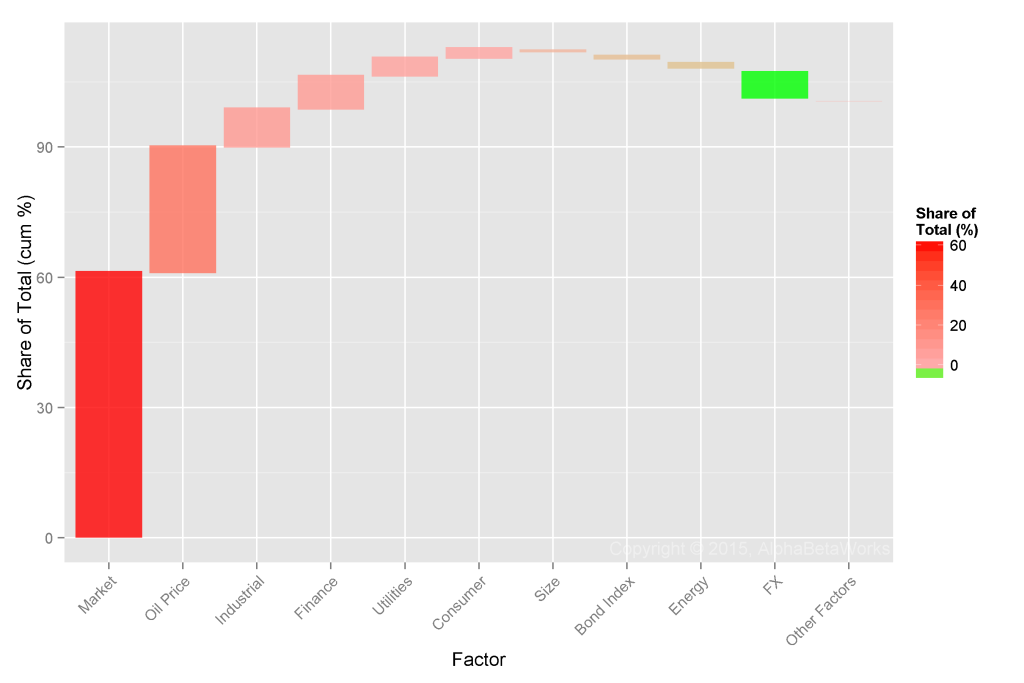

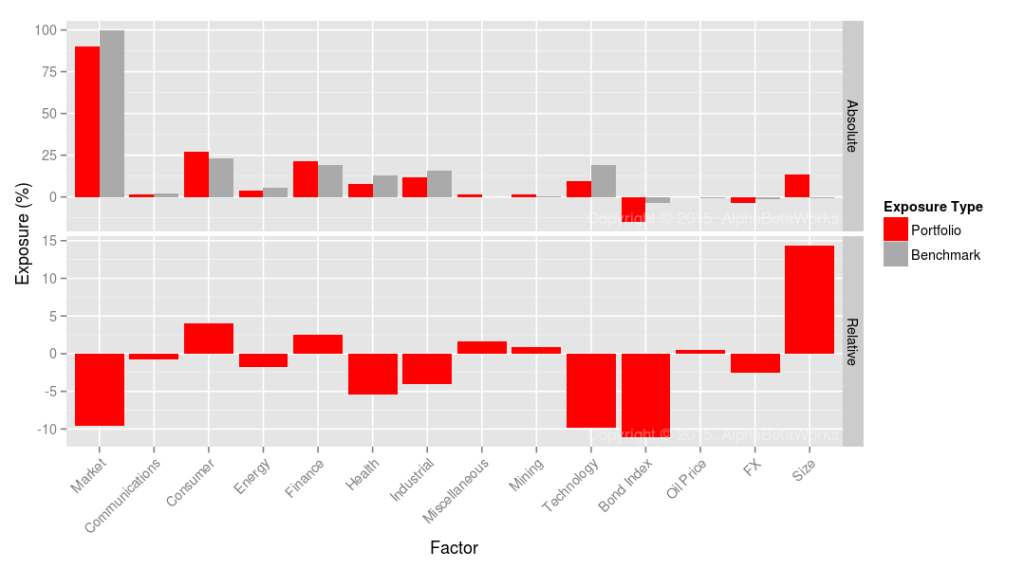

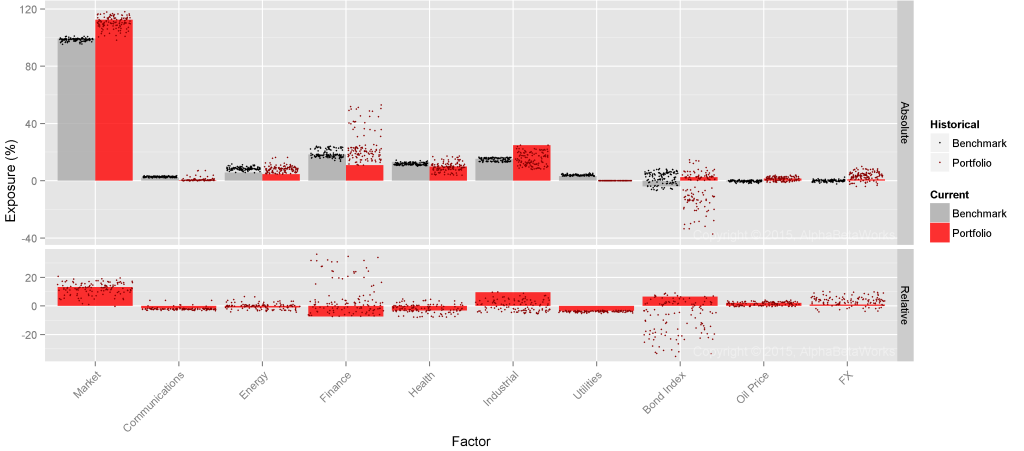

Below are this cluster’s significant factor exposures (in red) relative to the Russell 3000’s exposures (in gray):

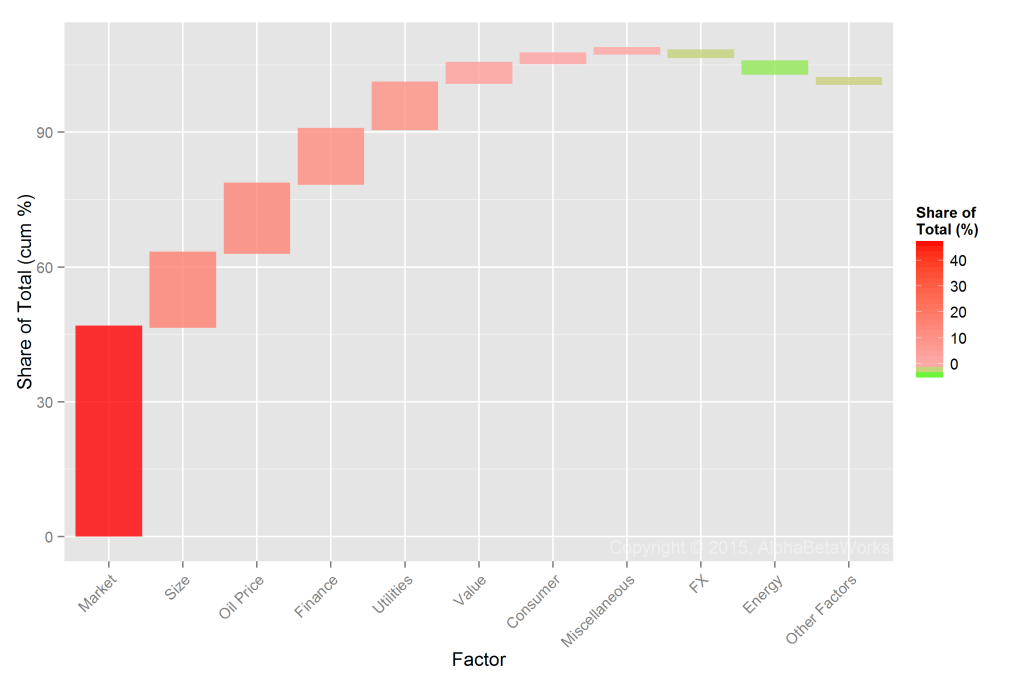

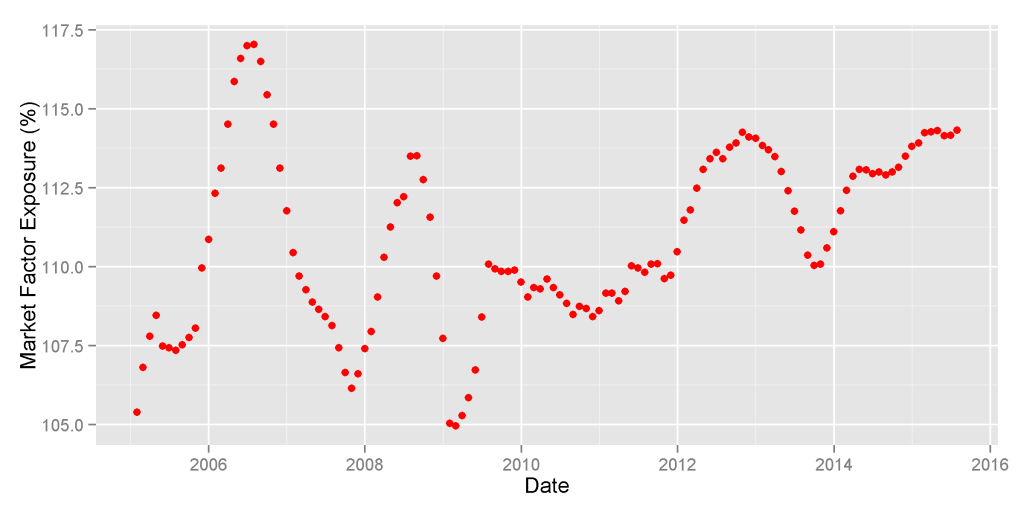

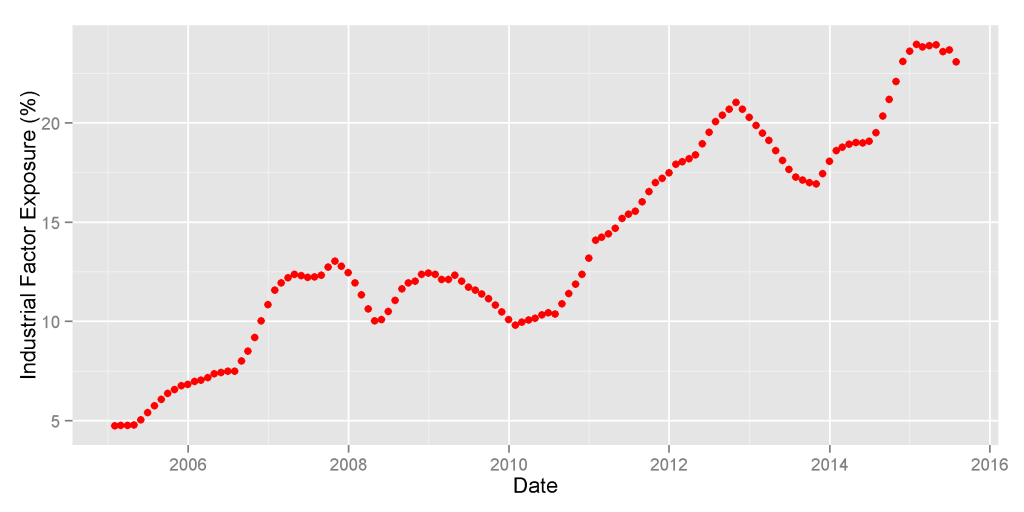

Market (high-beta) and Size (small-cap) exposures are responsible for most of this cluster’s relative factor risk:

| Factor |

Relative Exposure (%) |

Portfolio Variance (%²) |

Share of Systematic Variance (%) |

|

| Market |

5.18 |

0.44 |

46.48 |

|

| Size |

-4.65 |

0.16 |

16.46 |

|

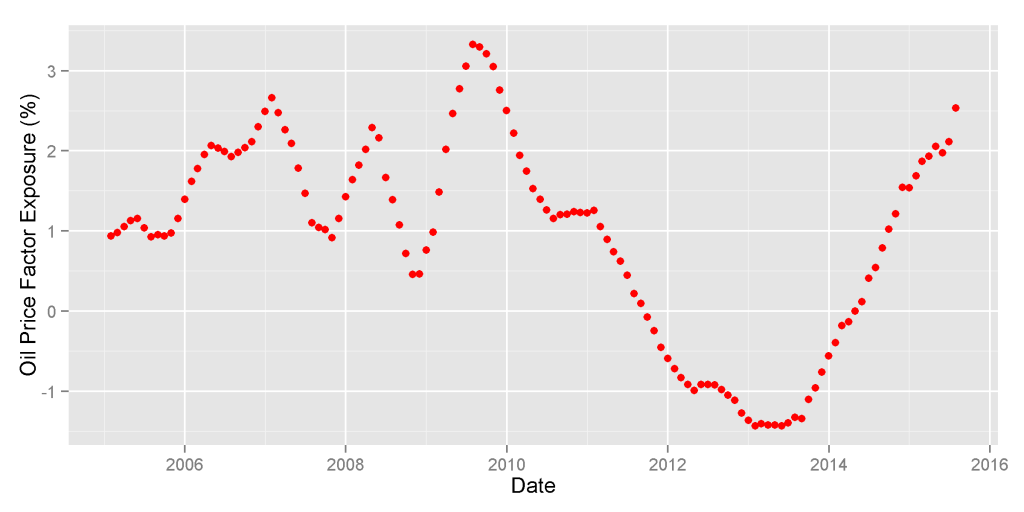

| Oil Price |

0.90 |

0.15 |

15.38 |

|

| Finance |

-5.61 |

0.12 |

12.19 |

|

| Utilities |

-2.58 |

0.10 |

10.29 |

|

| Other Factors |

-0.03 |

-0.80 |

||

| Total |

0.94 |

100.00 |

||

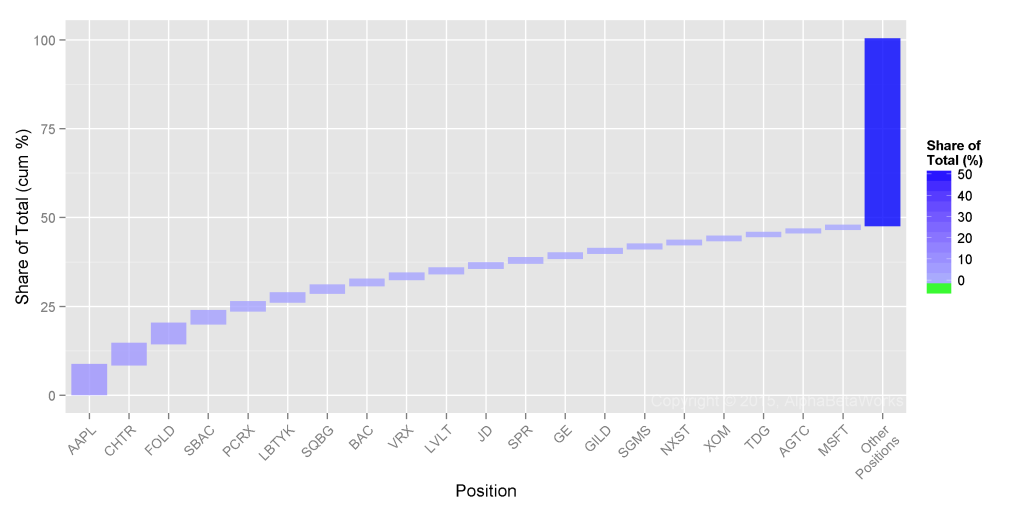

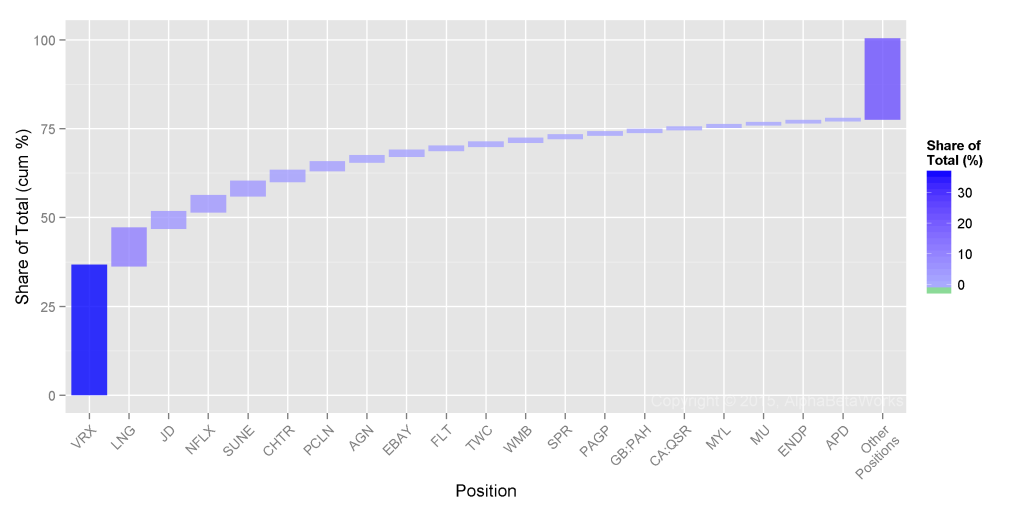

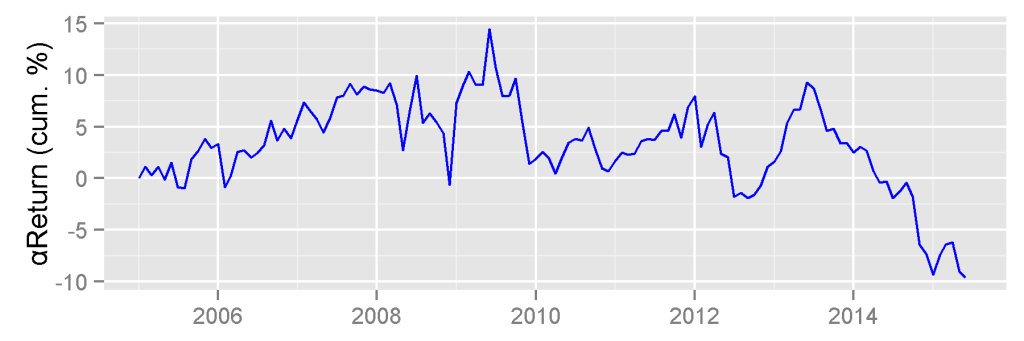

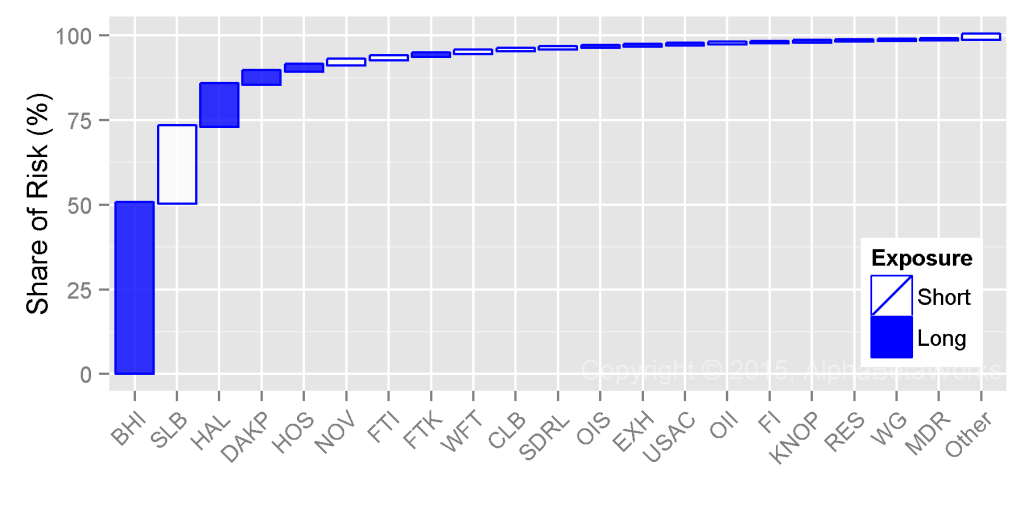

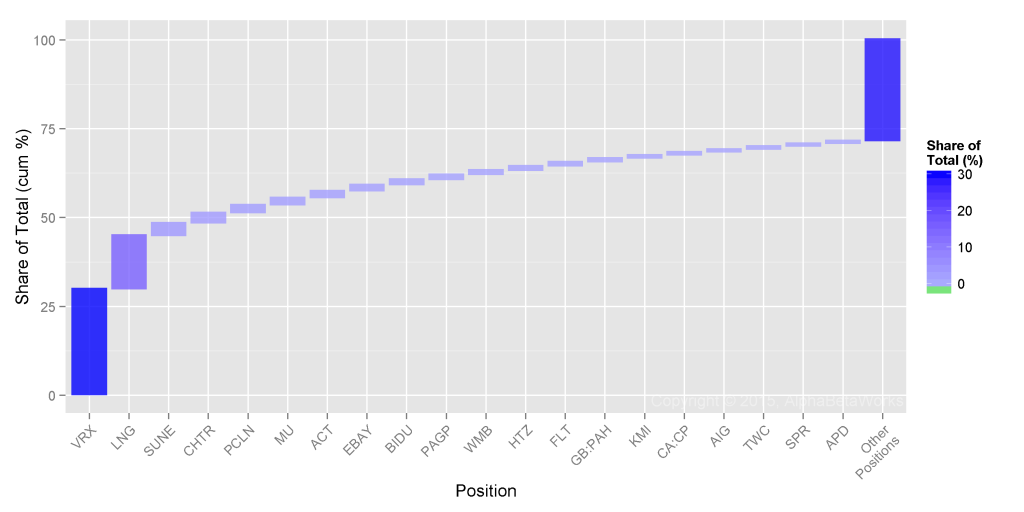

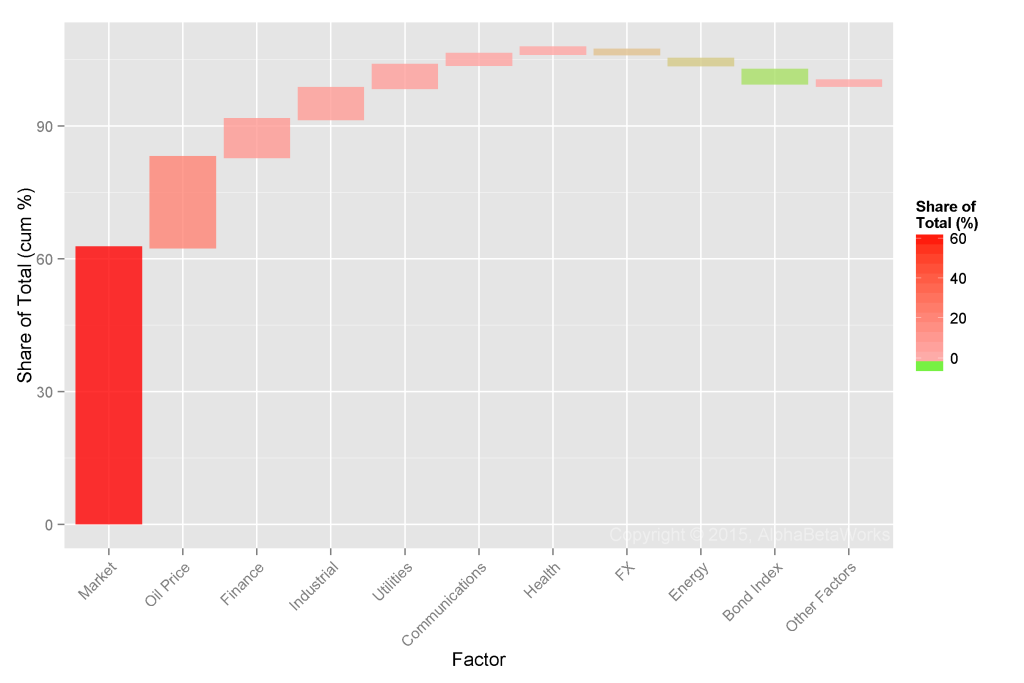

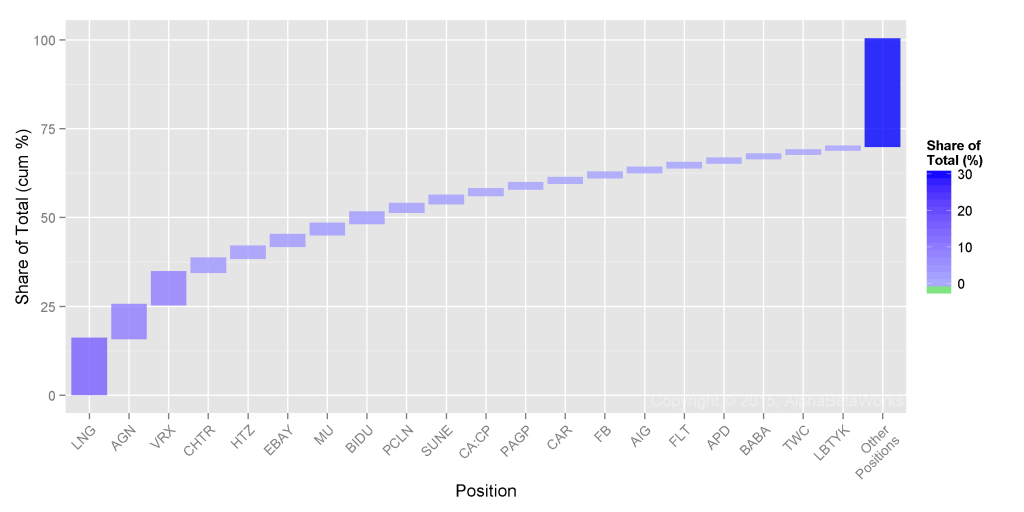

AQR-Adage Cluster Residual (Idiosyncratic) Crowding

There is less residual crowding in the AQR-Adage Cluster than in HF Aggregate. For HF Aggregate, just three stocks were responsible for over half of the relative residual risk in Q2 2015. By contrast, in the AQR-Adage Cluster, four stocks are responsible for approximately a quarter of the relative residual risk:

| Symbol | Name |

Exposure (%) |

Share of Idiosyncratic Variance (%) |

| AAPL | Apple Inc. |

-1.67 |

8.34 |

| CHTR | Charter Communications, Inc. Class A |

1.09 |

5.97 |

| FOLD | Amicus Therapeutics, Inc. |

0.35 |

5.60 |

| SBAC | SBA Communications Corporation |

1.40 |

3.57 |

| PCRX | Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

0.37 |

2.56 |

| LBTYK | Liberty Global Plc Class C |

1.08 |

2.47 |

| SQBG | Sequential Brands Group, Inc. |

0.09 |

2.16 |

| BAC | Bank of America Corporation |

-0.73 |

1.71 |

| VRX | Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. |

0.50 |

1.66 |

| LVLT | Level 3 Communications, Inc. |

0.41 |

1.45 |

Crowding within the AQR-Adage Cluster may not affect AAPL, CHTR, FOLD, and SBAC. However, these consensus bets will be the key contributors to the active returns of the AQR-Adage Cluster and many members. These stocks will also be the key drivers of some allocators’ idiosyncratic performance.

Idiosyncratic crowding is not the main problem with the cluster, since the expected idiosyncratic tracking error is low. Passivity is a bigger problem: Allocators to diversified portfolios of hedge funds within this cluster may be paying high fees for what’s effectively an index fund of passive factor bets. Closet indexing may be practiced by 70% of “active” U.S. mutual fund capital, but the high fees charged by hedge funds make fund differentiation especially important.

Summary

- An analysis of the underlying structure of hedge fund crowding reveals hedge fund clustering – groups of portfolios with similar bets.

- The largest hedge fund cluster consists of approximately 50 funds with shared factor and residual exposures.

- The largest cluster’s factor herding is towards Market (high-beta) and short Size (small-cap) exposures.

- This cluster’s residual herding is away from AAPL and towards CHTR, FOLD, and SBAC.

- Allocators unaware of the clustering of their funds may be paying active fees for an effectively passive factor portfolio.