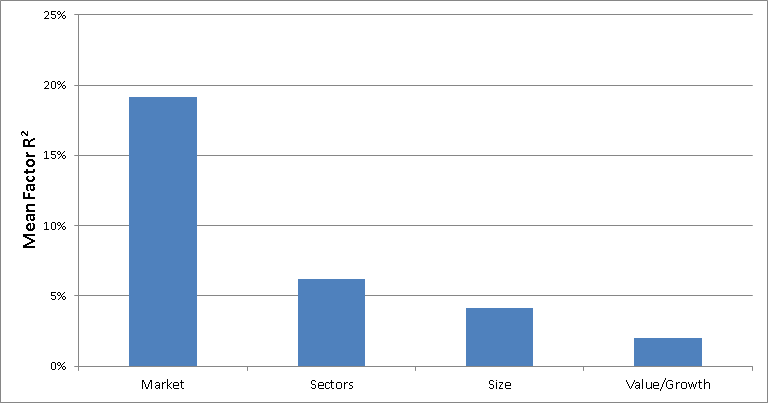

The proliferation of smart beta strategies has raised questions about the relationship between the core risk factors that have formed the foundation of quantitative investment analysis for decades and the growing factor zoo of strategies. Whereas some state that “smart beta is the vehicle to deliver factor investing” others argue that “factor tilts are not smart ‘smart beta’”. A central question is how well dumb beta factors such as Market, Sectors/Industries, and Style (Value/Growth, Big/Small) can replicate the zoo’s residents. The answers drive risk modeling, performance evaluation, and portfolio construction. This article studies replicating fundamental indexing with factor tilts over the past ten years and illustrates how well it has worked. We will discuss the other popular smart beta strategies in subsequent articles.

In this 10-year replication example, the reality falls between the extreme viewpoints above:

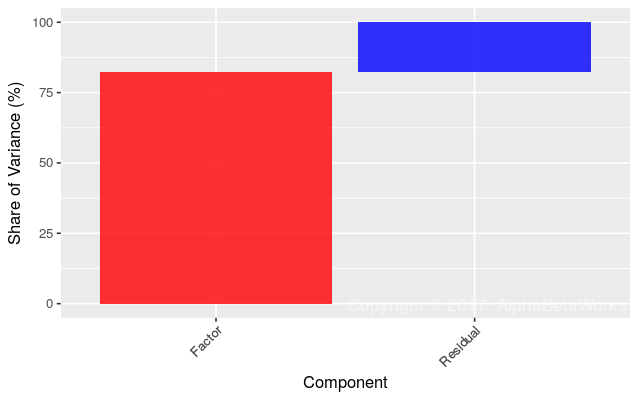

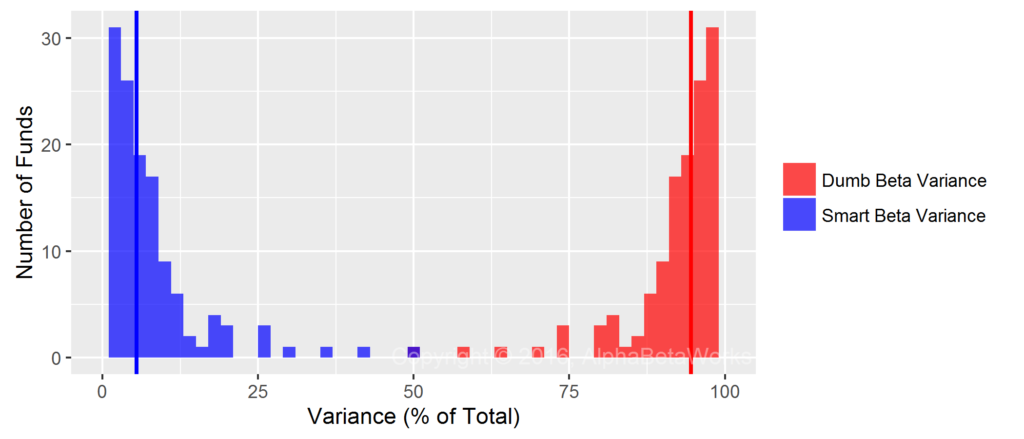

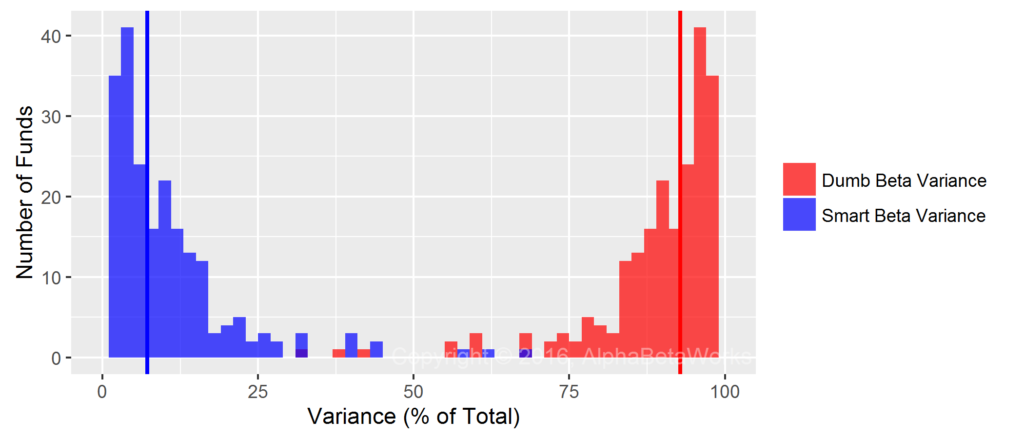

- Factor tilts replicate virtually all (>96%) of the absolute variance.

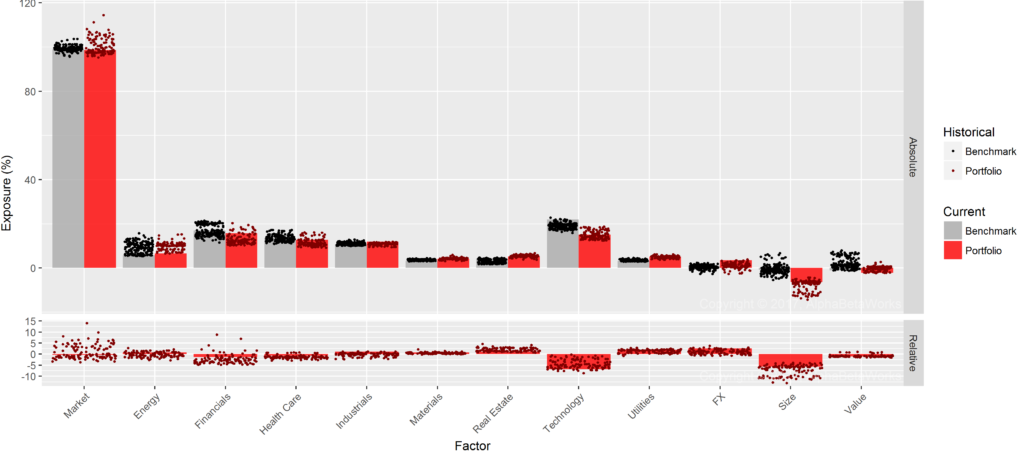

- In a typical market environment, factor tilts replicate most (60-75%) of the relative variance. In fact, in this environment, fundamental indexing is substantially replicated with sector rotation. Indeed, most U.S. and international smart beta strategies are largely instances of sector rotation.

- In periods of stress, factor tilts fail to replicate the relative variance.

- The difference in returns between the target and replicating portfolios is statistically insignificant.

- The relative return of the target and replicating portfolios does not follow a random walk – fundamental indexing goes through periods of outperformance and underperformance relative to the replicating portfolio.

We illustrate and quantify the systematic performance that is attainable, and the residual performance that is unattainable, when replicating fundamental indexing with a portfolio of atomic and liquid factor tilts. The replication uses only the rudimentary factors that most commercial equity risk models implement: Market, Sectors, and optionally Style. We also show the environments when replication is more or less successful. It is up to the user to determine whether a given tracking error is adequate for a given application.

Prior Research on Replication

When assumptions and idiosyncrasies of a factor replication exercise are not made explicit, confusion can arise. Any test replicating smart beta with dumb factor tilts is a joint test of the following components:

- The equity risk model and the optimizer used to create replicating factor tilt portfolios,

- The securities used to implement replicating portfolios,

- The portfolio constraints.

Failure of replication based on a flawed model or flawed factors (such as the simple three Fama-French factors suffering from multicollinearity) merely shows the replication process to be flawed; it does not prove the replication impossible.

Replicating Smart Beta Strategies with Dumb Factor Tilts

This article considers fundamental indexing as implemented by the PowerShares FTSE RAFI US 1000 Portfolio (PRF).

We constructed quarterly replicating portfolios using PRF’s position filings. We lagged positions by two months and risk model data by one month to account for filing and processing delays. For example, pre-1/31/2017 PRF positions and 2/28/2017 AlphaBetaWorks U.S. Equity Risk Model were used to construct the 3/31/2017 portfolio, which was next rebalanced on 6/30/2017. The optimizer aimed to minimize estimated future tracking error of the replicating portfolio to PRF, subject to portfolio constraints. Results were unaffected by changes in rebalance delay of a few months.

We attempted to use the simplest replication methodology that is practical and sound. Results vary depending on the security universe, the equity risk model, the optimizer, and the portfolio parameters.

Replicating Fundamental Indexing with Market and Sector Factor Tilts

Market and Sector Factor portfolios were constructed using a Market ETF and nine top-level sector ETFS:

| SPY |

SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust |

| XLY |

Consumer Discretionary Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLP |

Consumer Staples Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLE |

Energy Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLF |

Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLV |

Health Care Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLI |

Industrial Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLB |

Materials Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLK |

Technology Select Sector SPDR Fund |

| XLU |

Utilities Select Sector SPDR Fund |

Position constraint for Sector ETFs was 0 to +100%, and for SPY -100% to +100%. Negative Market weight is necessary to target Market exposures that are not attainable by a long-only portfolio of Sector ETFs. Advanced sector indices, such as the NYSE Pure Exposure Indices, avoid this problem and enable long-only replicating portfolios targeting any combination of exposures.

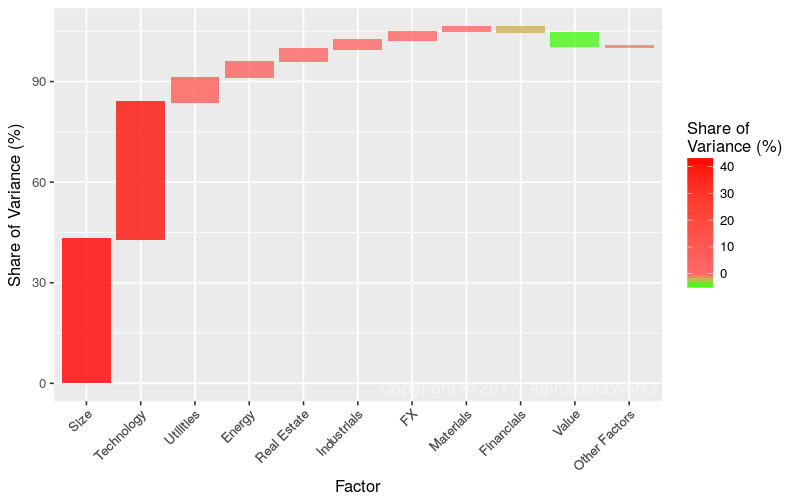

Fundamental Indexing vs. Market and Sector Tilts: Absolute Performance

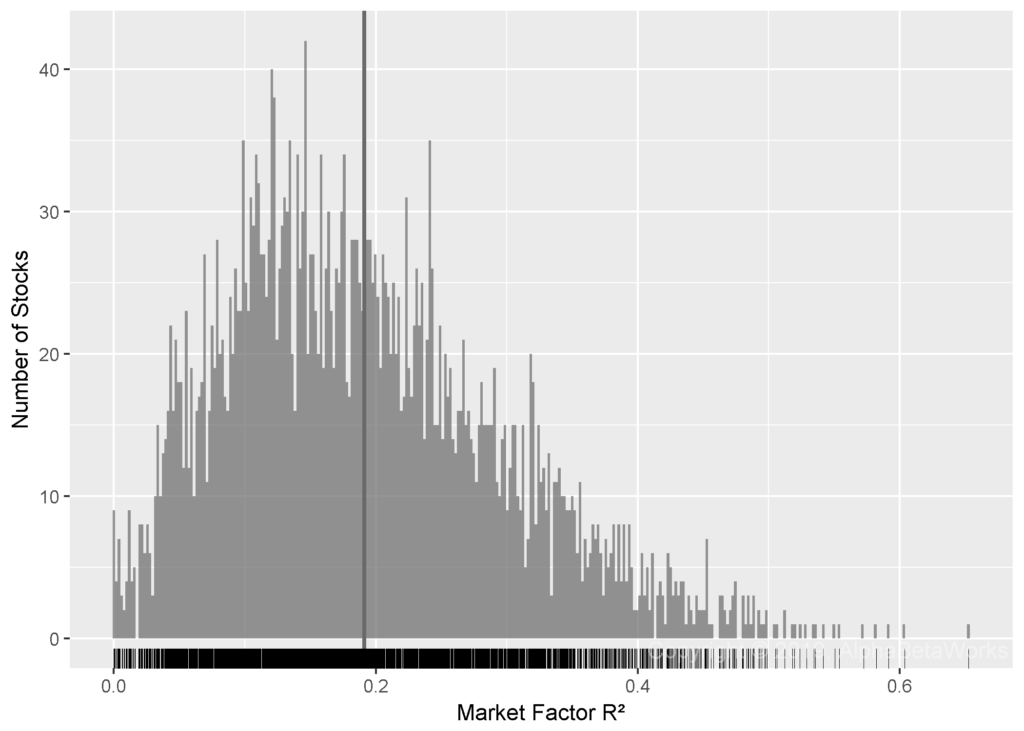

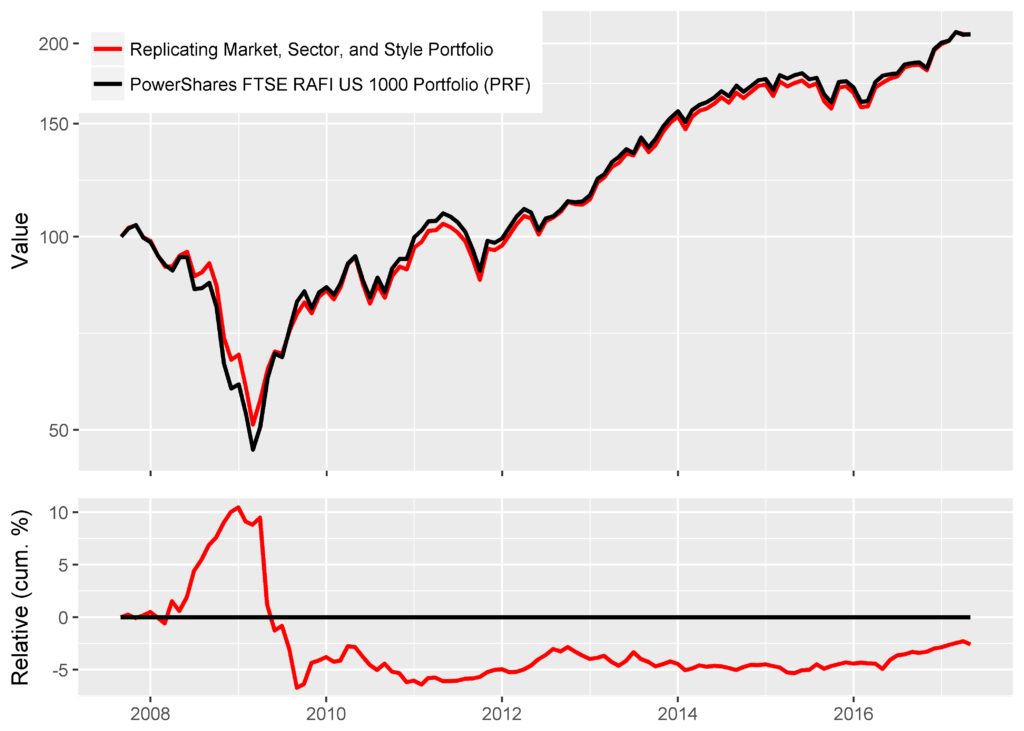

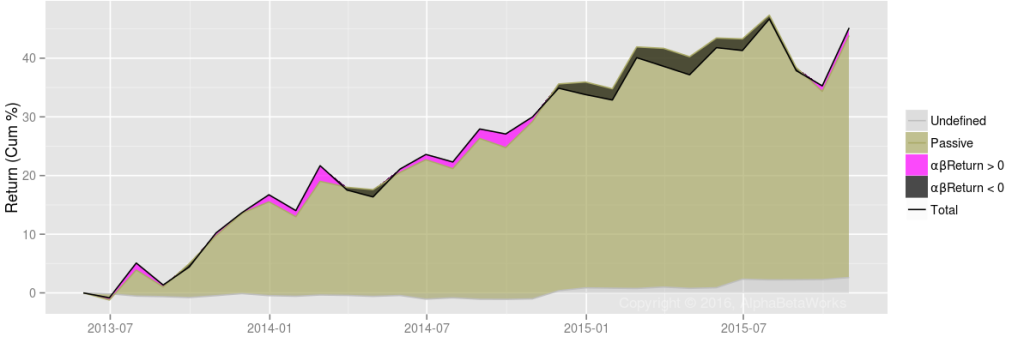

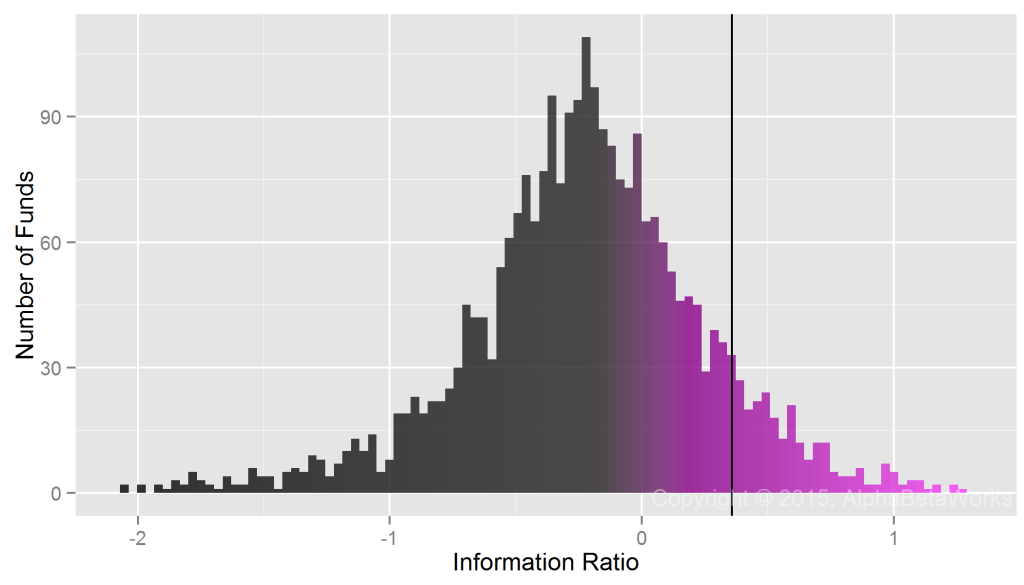

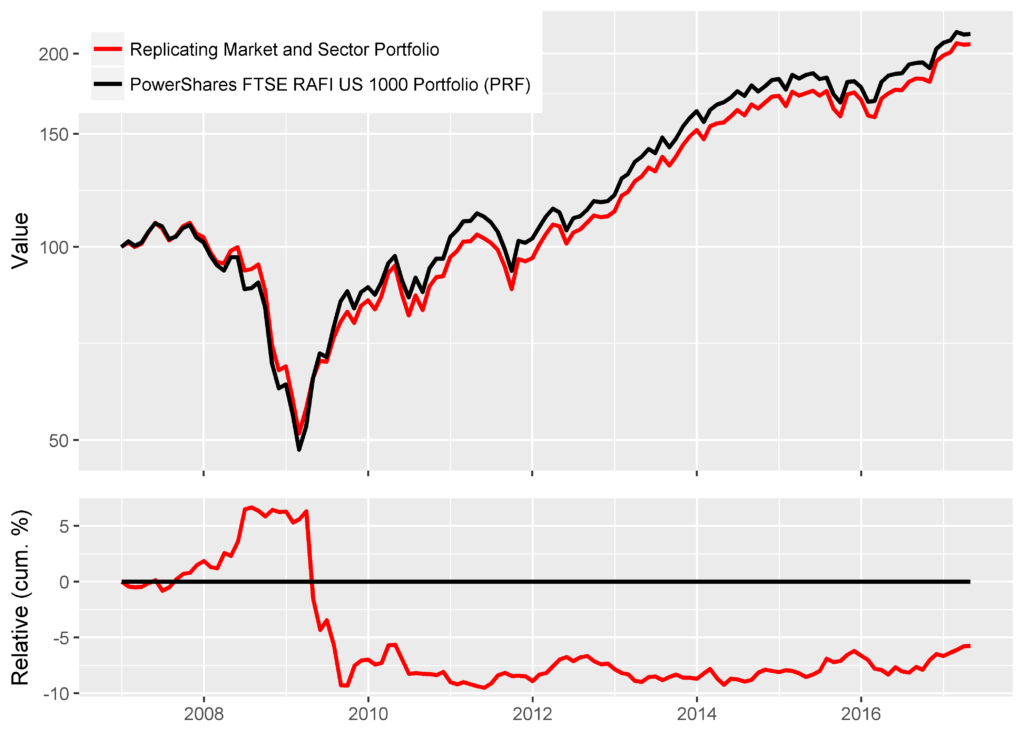

The following chart plots cumulative and relative returns for the fundamental indexing portfolio and the replicating Market and Sector Factor portfolio:

Replicating fundamental indexing with Market and Sector Factor tilts: absolute performance

R-squared 0.9615

Correlation 0.9805

Tracking Error 3.50%

We performed a t-test on the difference in monthly log returns to determine whether they are statistically different from zero:

t = -0.3439

p-value = 0.7315

95 percent confidence interval = (-0.1976, 0.1391)

sample estimate mean = -0.0293

We also performed a Ljung-Box Test on the difference in monthly log returns to determine whether it is a random walk (specifically, whether there are non-0 autocorrelations of the time series):

X-squared = 6.0837

p-value = 0.0136

Though the mean difference in log returns is not statistically different from 0, relative performance is not a random walk. The relative returns of PRF and the replicating portfolio are autocorrelated, as is evident in the chart above.

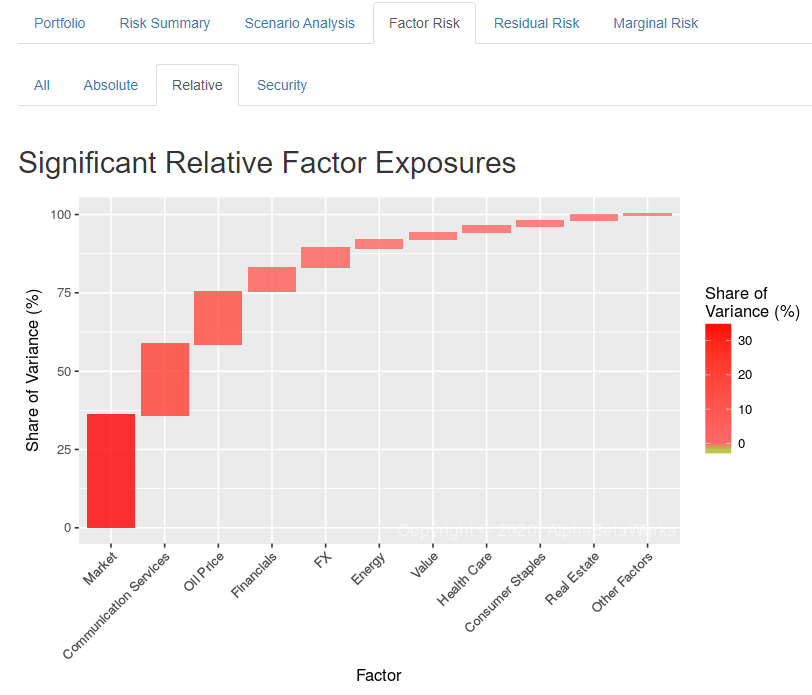

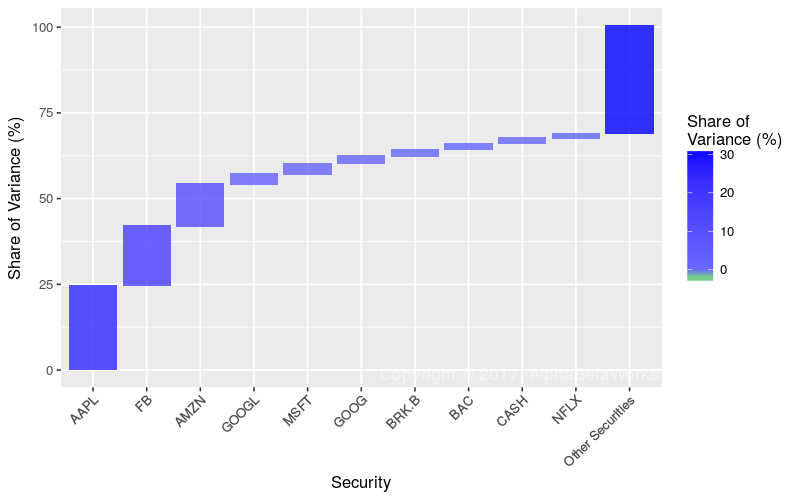

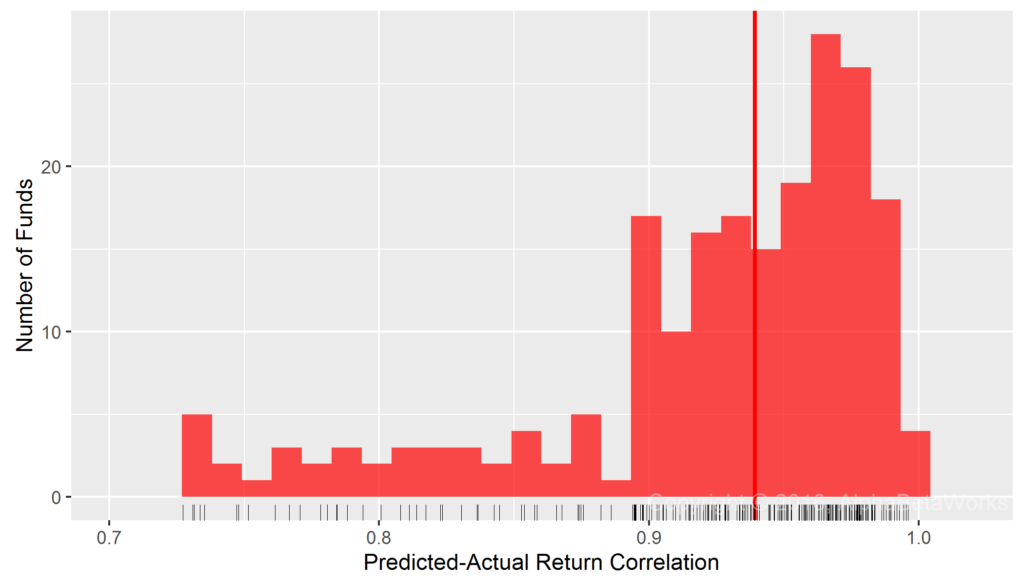

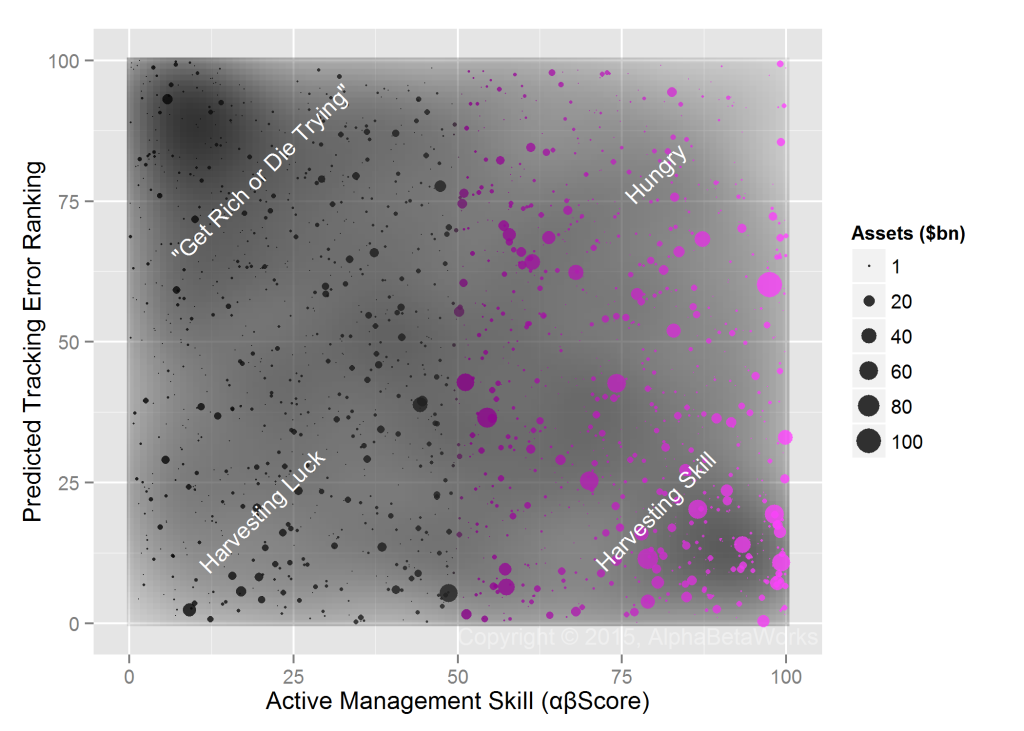

Fundamental Indexing vs. Market and Sector Tilts: Relative Performance

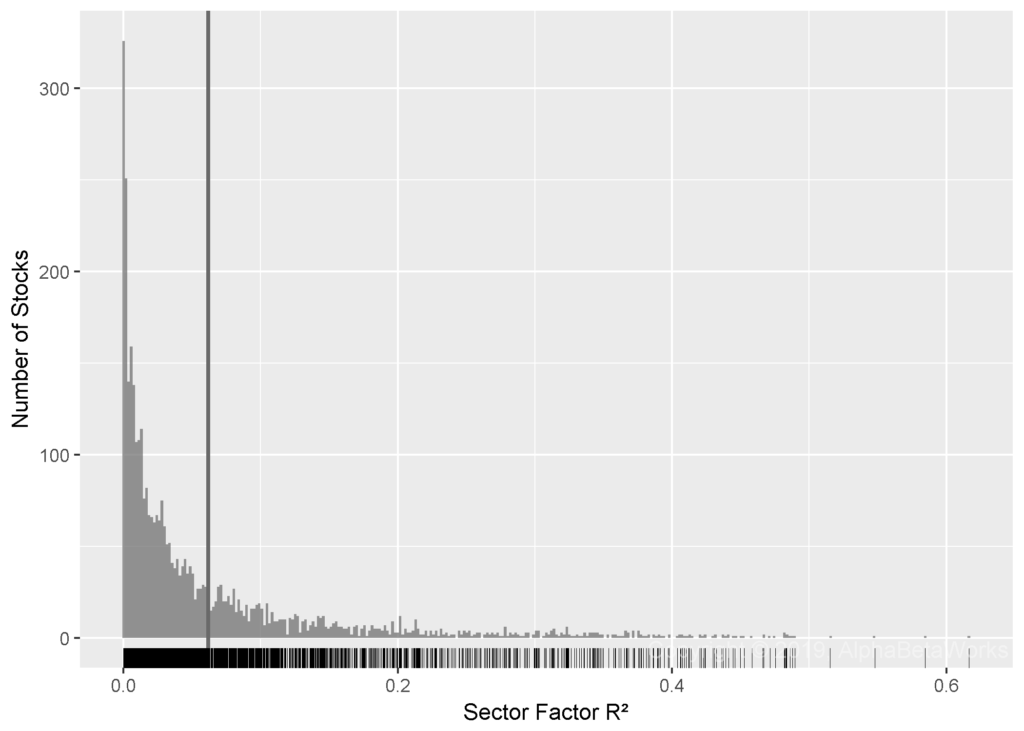

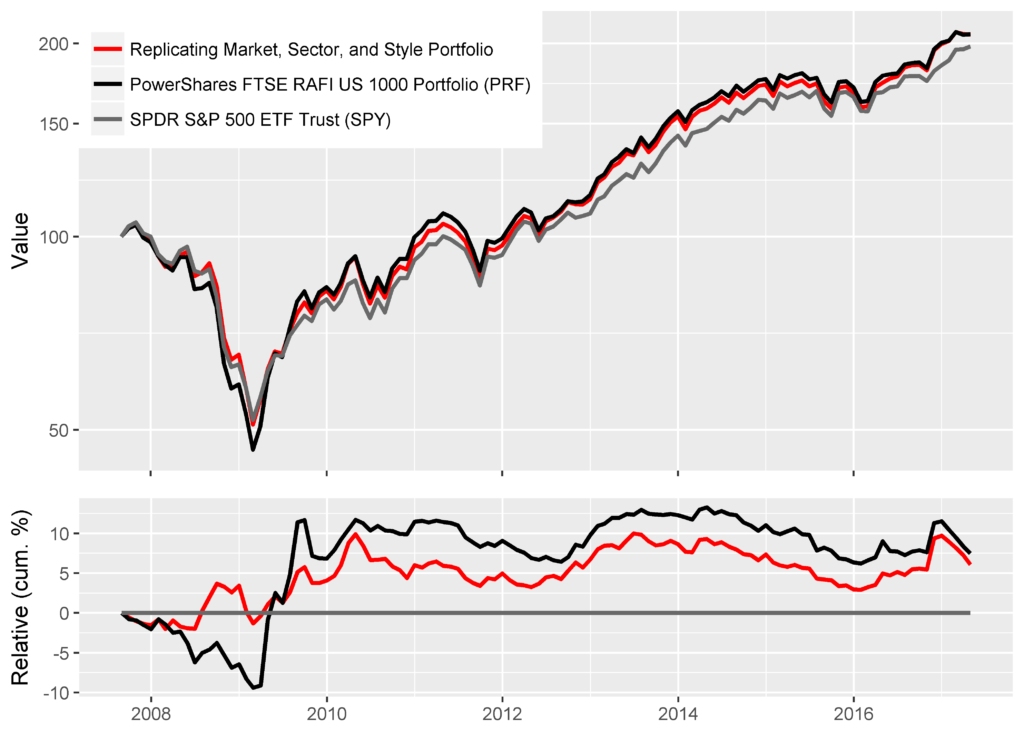

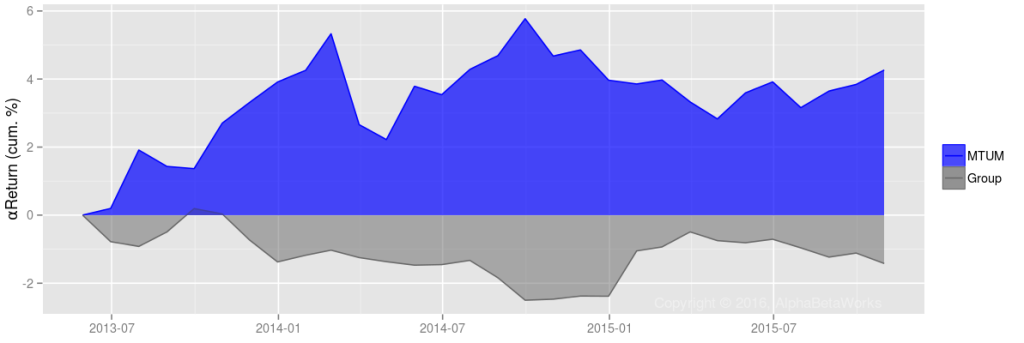

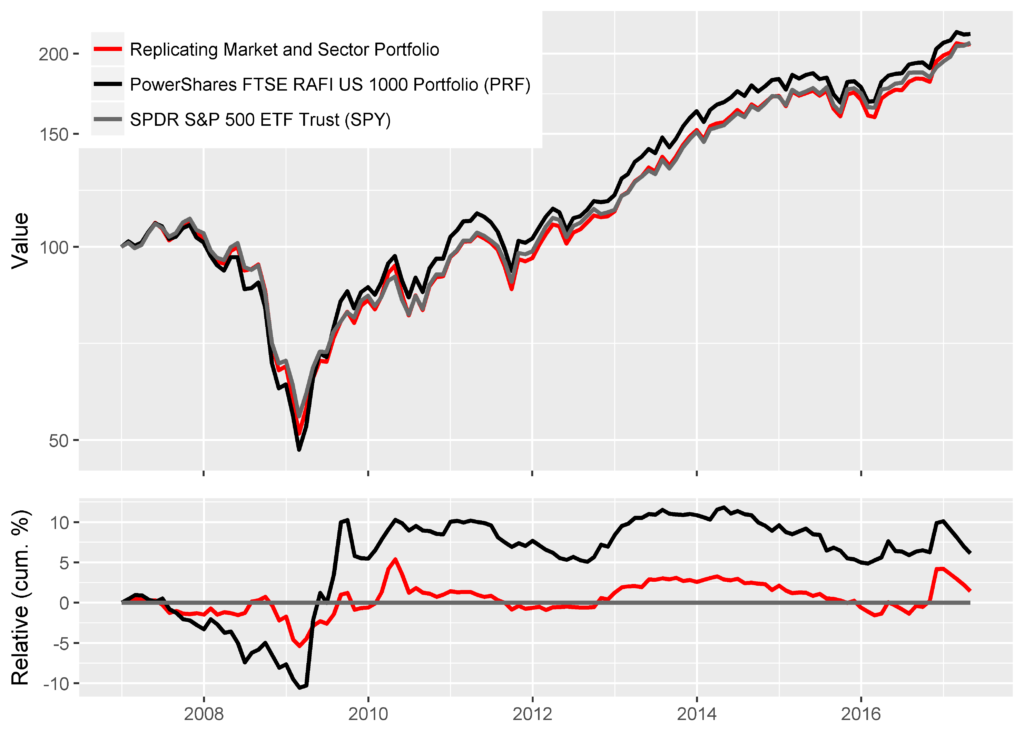

The following chart plots cumulative and relative returns for the fundamental indexing portfolio, the replicating Market and Sector Factor portfolio, and the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY):

Replicating fundamental indexing with Market and Sector Factor tilts: relative performance

R-squared 0.4929

Correlation 0.7020

Tracking Error 3.50%

Performance difference mostly comes from a few months during the 2008-2009 crisis when residual variance spikes. The replicating portfolio first sharply outperforms and then sharply underperforms. In a calmer environment post-2009, the fit is much closer:

R-squared 0.6124

Correlation 0.7825

Tracking Error 1.75%

Replicating Fundamental Indexing with Market, Sector, and Style Factor Tilts

Market, Sector, and Style Factor tilt portfolios add a Growth/Value ETF pair and a Small-Cap ETF to capture the additional Style Factor exposures:

| IWF |

iShares Russell 1000 Growth ETF |

| IWD |

iShares Russell 1000 Value ETF |

| IWM |

iShares Russell 2000 ETF |

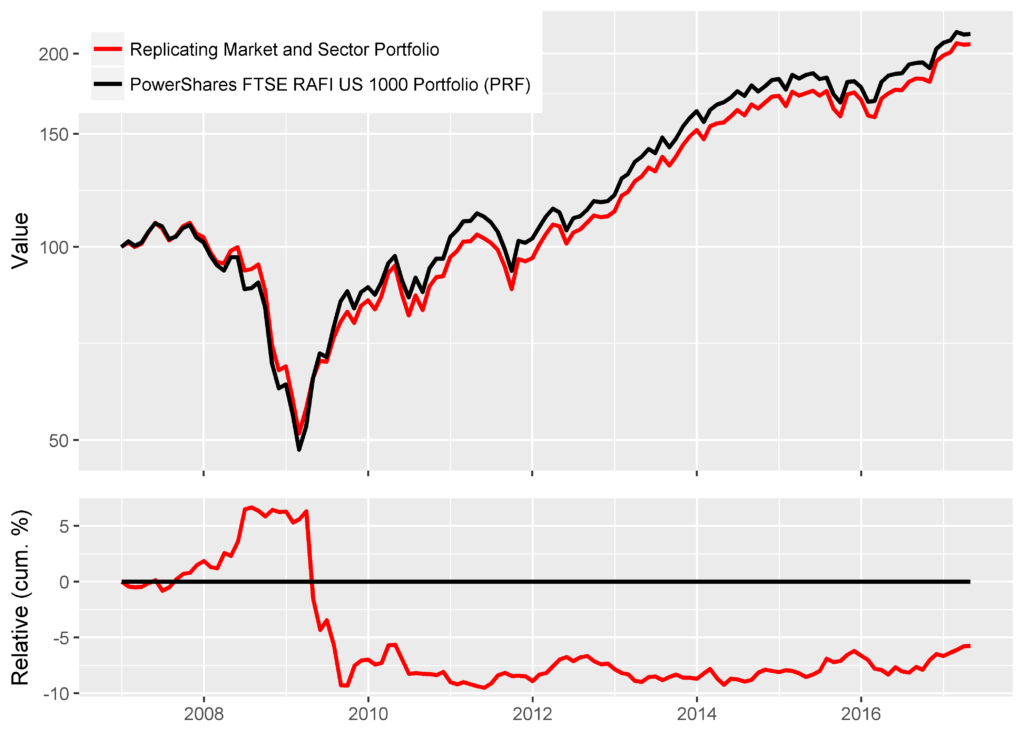

Fundamental Indexing vs. Market, Sector, and Style Tilts: Absolute Performance

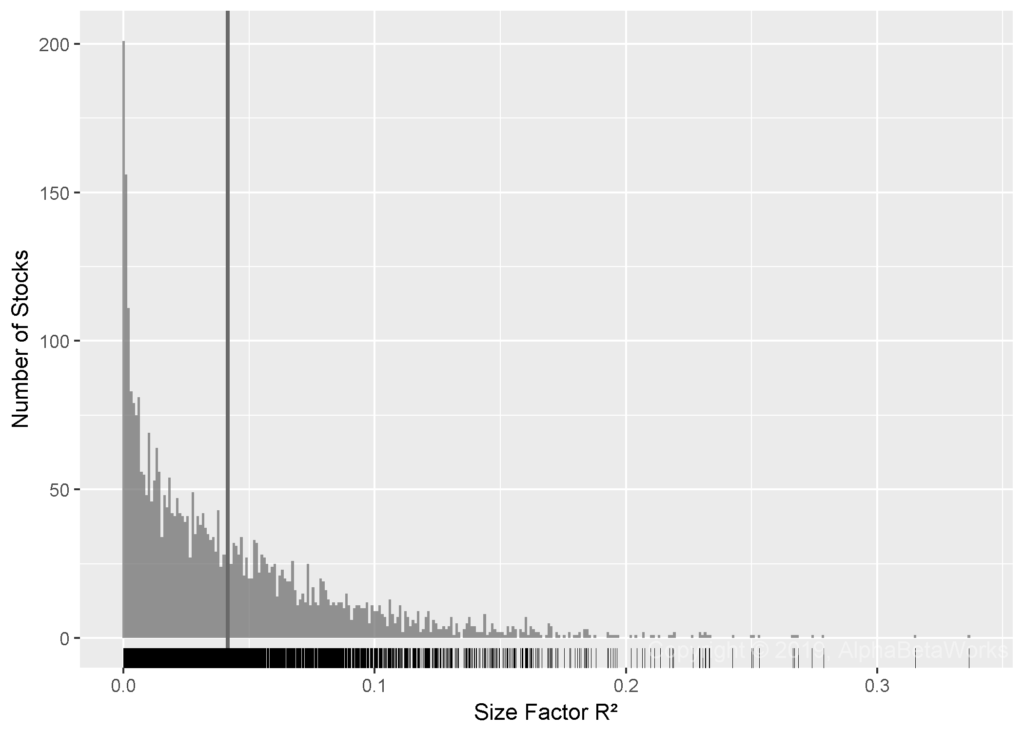

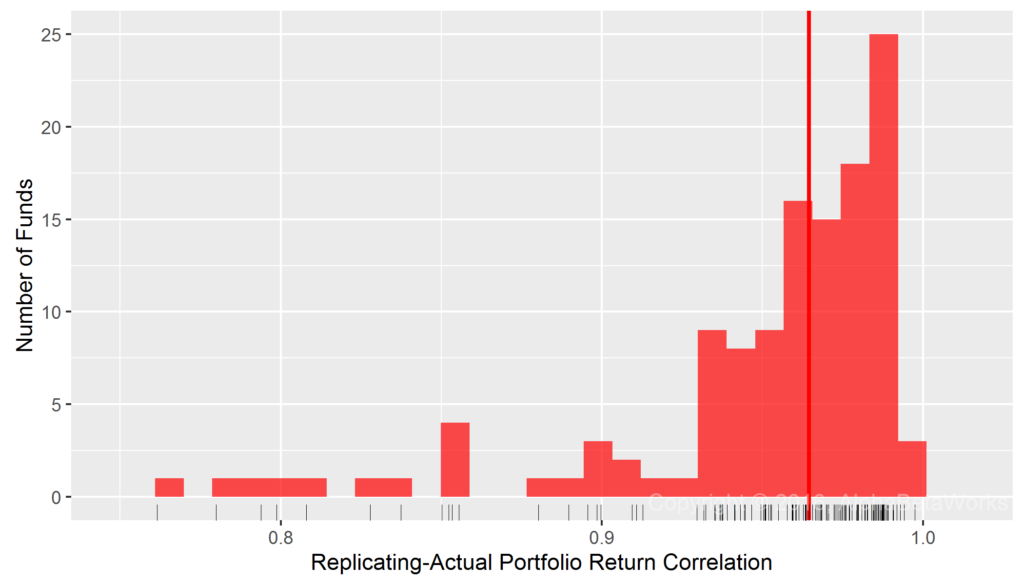

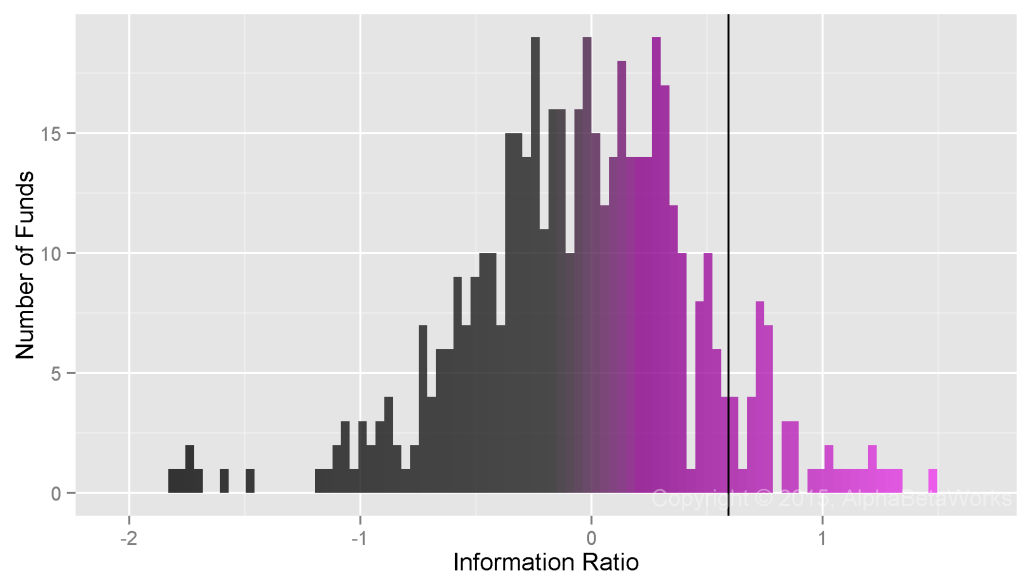

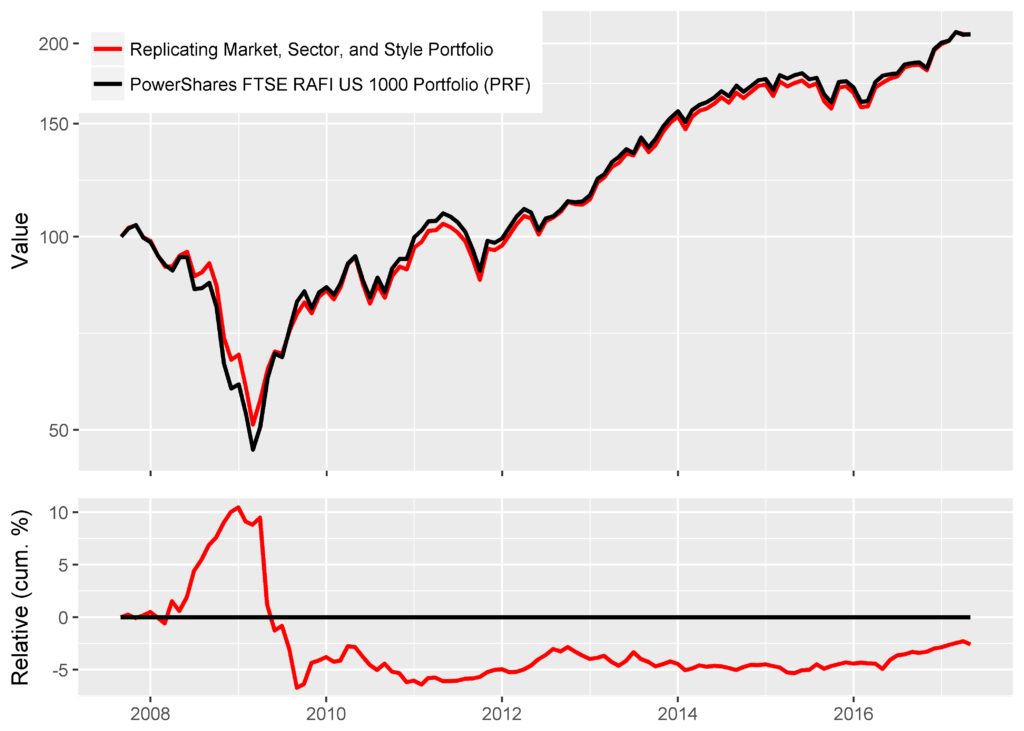

The following chart plots cumulative and relative returns for a fundamental indexing portfolio and the replicating Market, Sector, and Style Factor portfolio:

Replicating fundamental indexing with Market, Sector, and Style Factor tilts: absolute performance

R-squared 0.9619

Correlation 0.9807

Tracking Error 3.61%

The t-test results are similar to those of the Market and Sector replicating portfolio:

t = -0.0062504

p-value = 0.995

95 percent confidence interval = (-0.1802, 0.1791)

sample estimate mean = -0.0006

The Ljung-Box test results are also similar:

X-squared = 6.1228

p-value = 0.0134

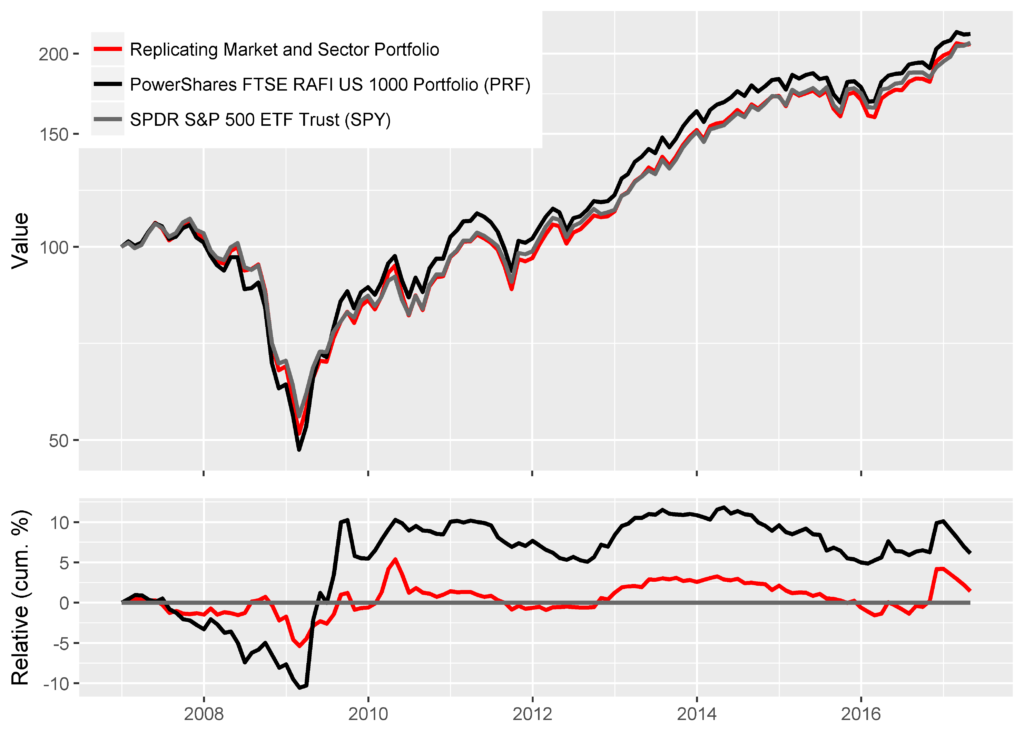

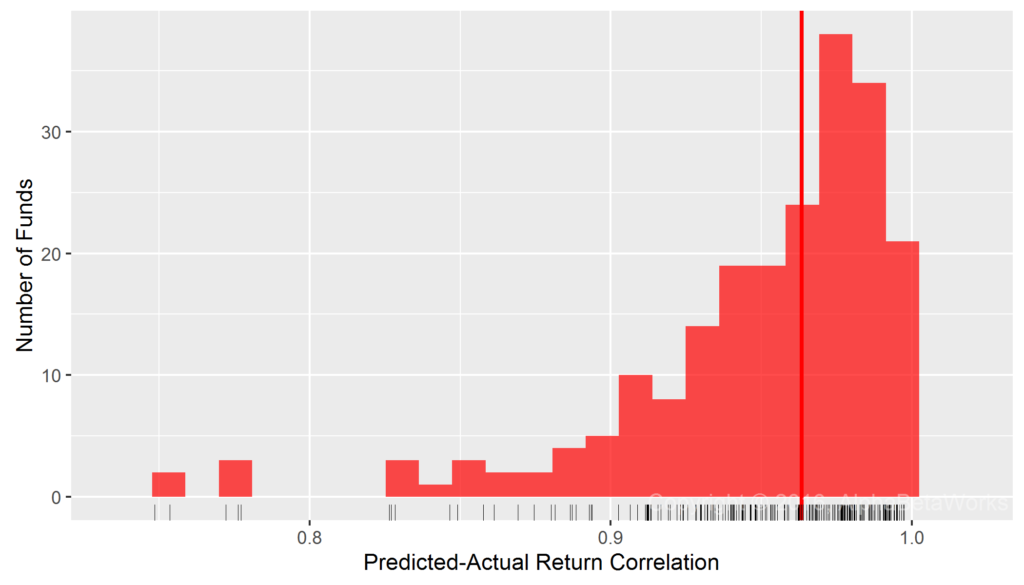

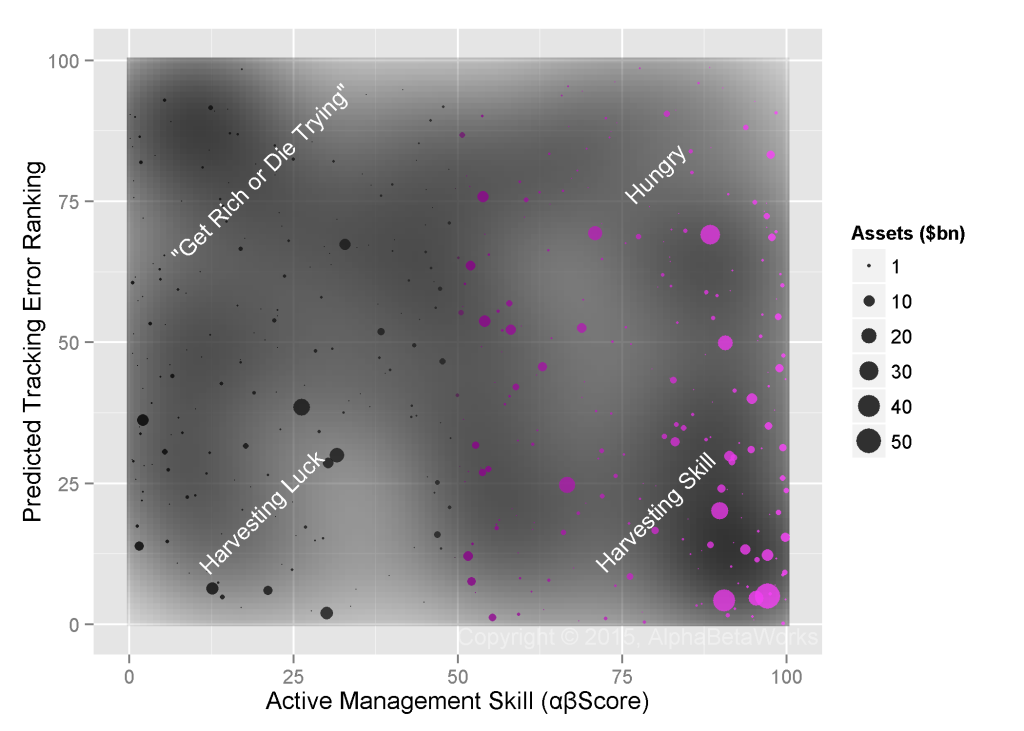

Fundamental Indexing vs. Market, Sector, and Style Tilts: Relative Performance

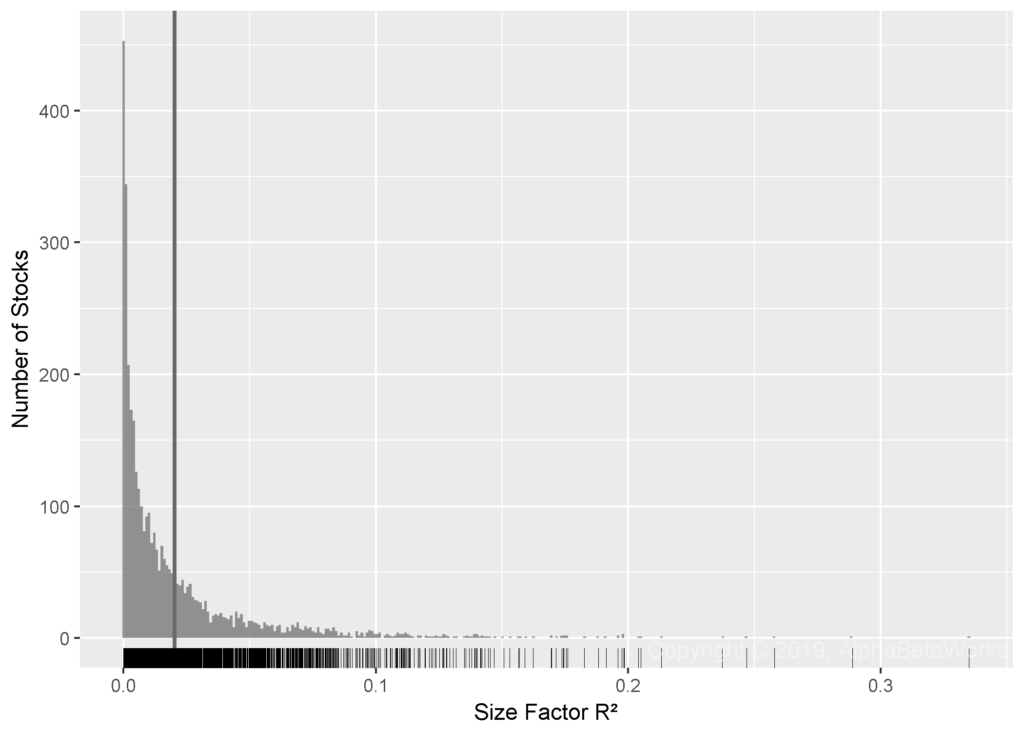

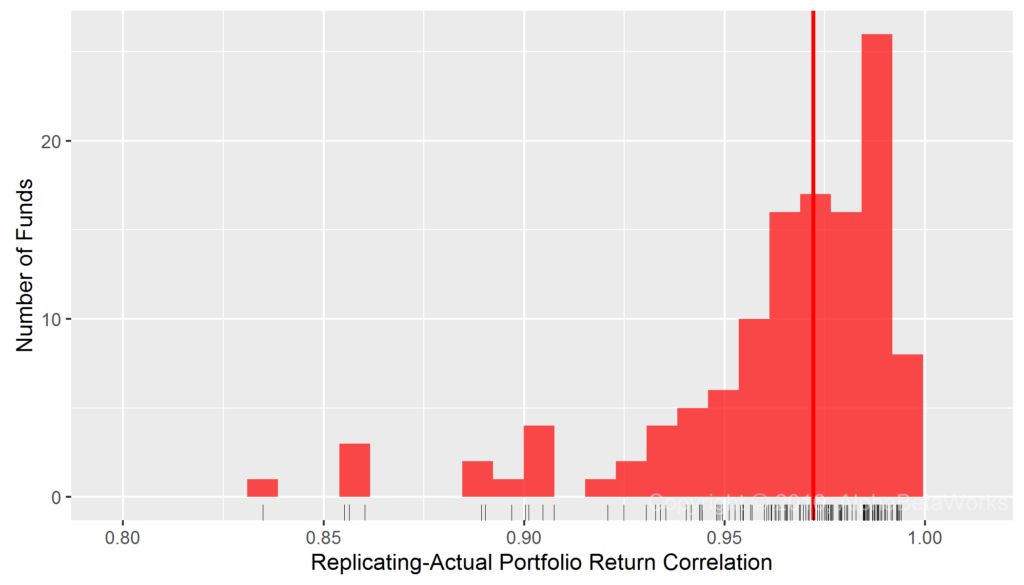

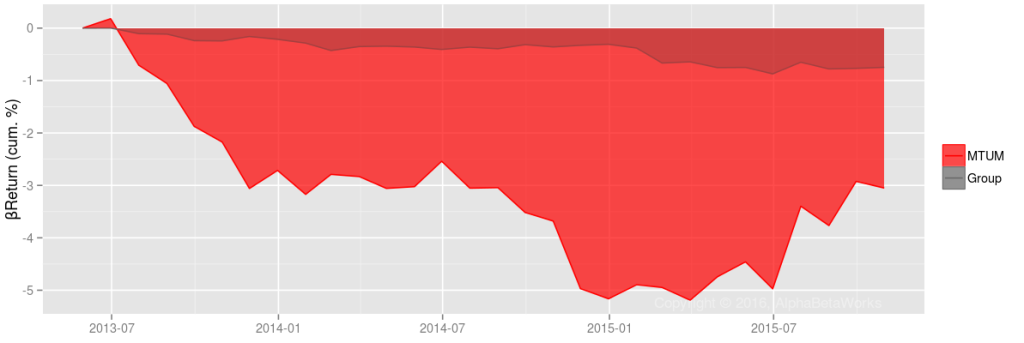

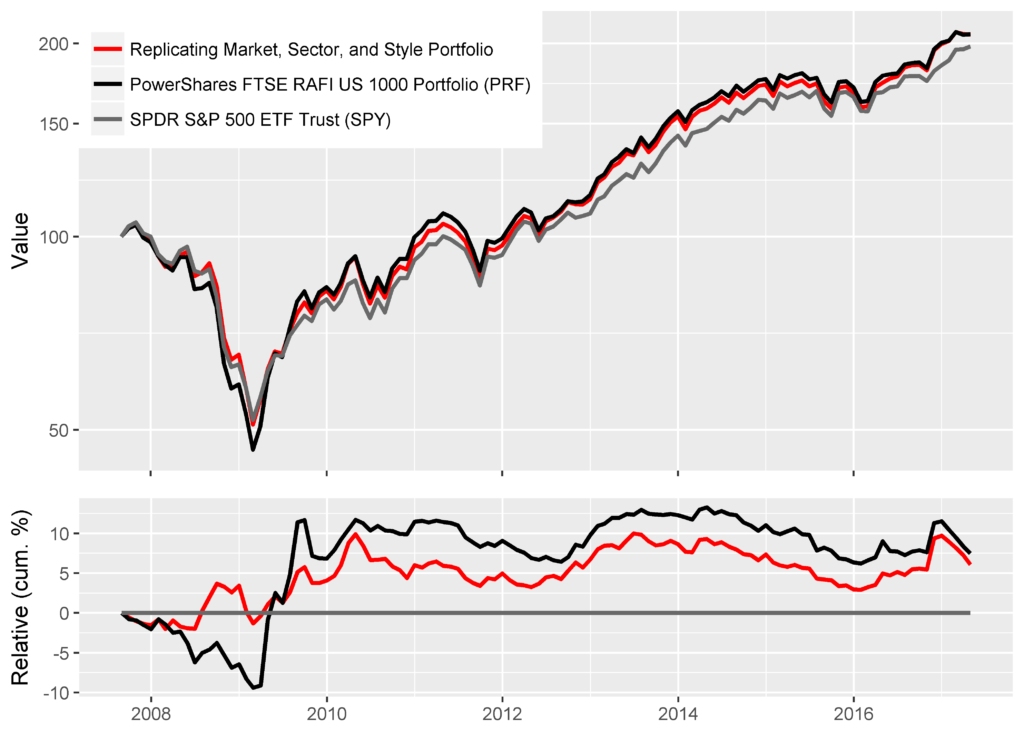

The following chart plots cumulative and relative returns for the fundamental indexing portfolio, the replicating Market, Sector, and Style Factor portfolio, and SPY:

Replicating fundamental indexing with Market, Sector, and Style Factor tilts: relative performance

Over the entire 10-year history, the style factors do not materially change the quality of replication:

R-squared 0.4794

Correlation 0.6924

Tracking Error 3.61%

Post-2009, the style factors do improve the fit:

R-squared 0.7501

Correlation 0.8661

Tracking Error 1.44%

Conclusions

- Whether the tracking error of replication is acceptable depends on the application.

- Though fully replicating fundamental indexing without any residual tracking error is impossible, even simple Market and Sector factor tilts replicate over 96% of the absolute variance for the fundamental indexing portfolio over the past ten years.

- In a normal market environment, factor tilts replicate most (60-75%) of the relative variance for the fundamental indexing portfolio.

- In periods of market stress, the tracking error of the replicating portfolio relative to the target is substantial.

- The difference in returns between the target and replicating portfolios is statistically insignificant, but it does not follow a random walk and exhibits cycles.

The information herein is not represented or warranted to be accurate, correct, complete or timely.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Copyright © 2012-2017, AlphaBetaWorks, a division of Alpha Beta Analytics, LLC. All rights reserved.

Content may not be republished without express written consent.