Active Share is a popular metric that purports to measure portfolio activity. Though Active Share’s fragility and ease of manipulation are increasingly well-understood, there has been no research on its predictive power. This paper quantifies the predictive power of Active Share and finds that, though Active Share is a statistically significant predictor of the performance difference between portfolio and benchmark (there is a relationship between Active Share and how active a fund is relative to a given benchmark), it is a weak one. The relationship explains only about 5% of the variation in activity across U.S. equity mutual funds. The predictive power of Active Share is a small fraction of that achieved with robust and predictive equity risk models.

The Breakdown of Active Share

Active Share — the absolute percentage difference between portfolio and benchmark holdings – is a common metric of fund activity. The flaws of this measure are evident from some simple examples:

- If a fund with S&P 500 benchmark buys SPXL (S&P 500 Bull 3x ETF), it becomes more passive and more similar to its benchmark, yet its Active Share increases.

- If a fund uses the S&P 500 as its benchmark but indexes Russell 2000, it is passive, yet its Active Share is 100%.

- If a fund differs from a benchmark by a single 5% position with 20% residual (idiosyncratic, stock-specific) volatility, and another fund differs from the benchmark by a single 10% position with 5% residual volatility, the second fund is less active, yet it has a higher Active Share.

- If a fund holds a secondary listing of a benchmark holding that tracks the primary holding exactly, it becomes no more active, yet its Active Share increases.

Given the flows above, the evidence that Active Share funds that outperform may merely index higher-risk benchmarks is unsurprising.

Measuring Active Management

A common defense is that these criticisms are pathological or esoteric, and unrepresentative of the actual portfolios. Such defense asserts that Active Share measures active management of real-world portfolios.

Astonishingly, we have not seen a single paper assess whether Active Share has any effectiveness in doing what it is supposed to do – identify which funds are more and which are less active. This paper provides such an assessment.

We consider two metrics of fund activity: Tracking Error and monthly active returns (measured as Mean Absolute Difference between portfolio and benchmark returns). Both these metrics measure how different the portfolios are in practice. Whether Active Share measures actual fund activity depends on whether it can differentiate among more and less active funds.

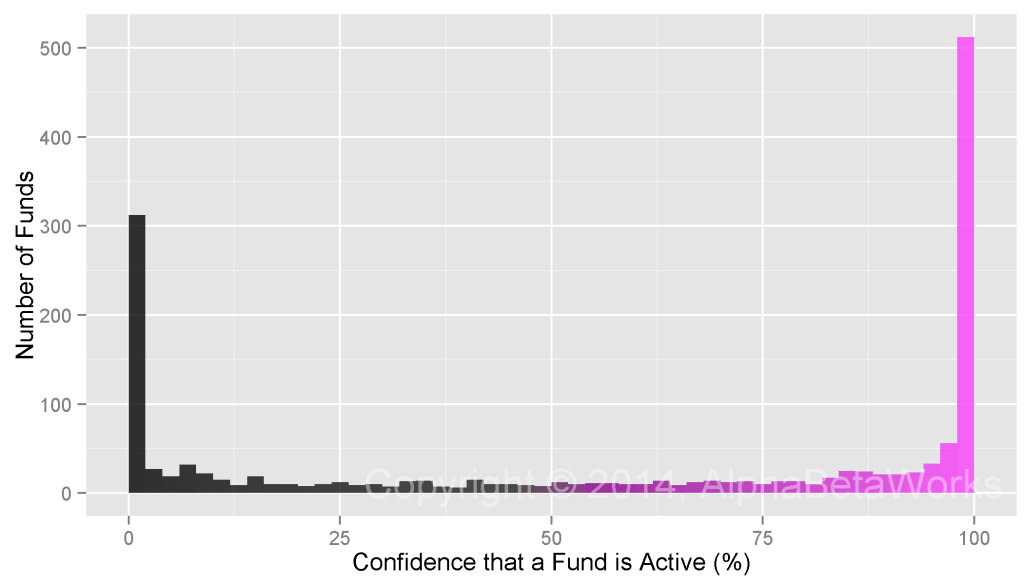

The study dataset comprises portfolio histories of approximately 3,000 U.S. equity mutual funds that are analyzable from regulatory filings. The funds all had 2-10 years of history. Our study uses the bootstrapping statistical technique – we select 10,000 samples and perform the following steps for each sample:

- Select a random fund F and a random date D.

- Calculate Active Share of F to the S&P 500 ETF (SPY) at D.

- Keep only those samples with Active Share between 0 and 0.75. This filter ensures that SPY may be an appropriate benchmark, and excludes small- and mid-capitalization funds that share no holdings with SPY. Such funds would all collapse into a single point with Active Share of 100, impairing statistical analysis.

- Measure the activity of F for the following 12 months (period D to D + 12 months). We determine how active a fund is relative to a benchmark by quantifying how similar its performance is to that of the benchmark.

After the above steps, we have 10,000 observations of fund activity as estimated by Active Share versus the funds’ actual activity for the subsequent 12 months.

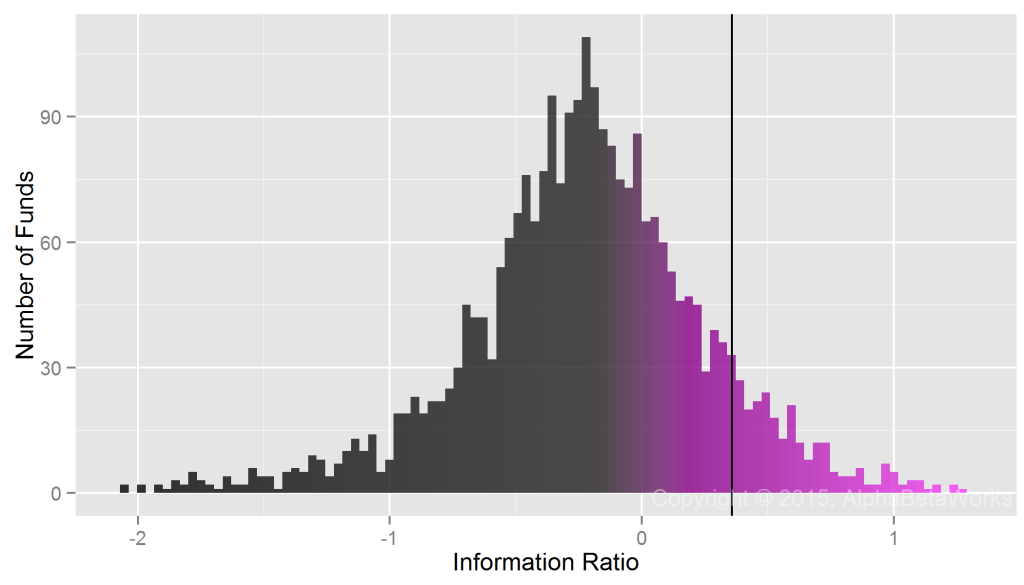

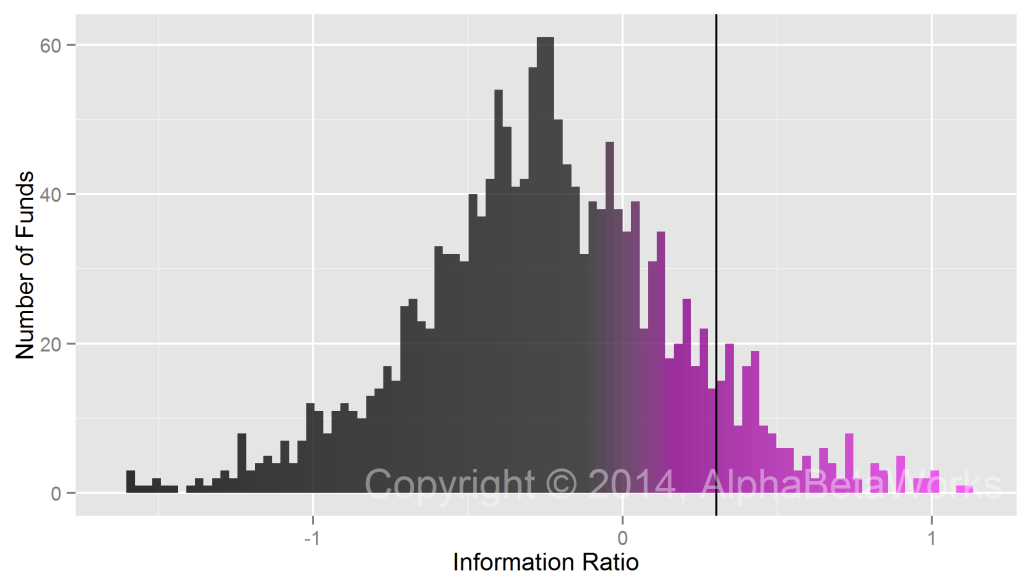

The Predictive Power of Active Share for U.S. Equity Mutual Funds

The following results quantify the predictive power of Active Share to differentiate among more and less active U.S. equity mutual funds. For perspective, we also include results on the predictive power of robust equity risk models. These results illustrate the relative weakness of Active Share as a measure of fund activity. They also indicate that, far from mitigating legal risk by reliance upon a claimed “best practice,” the use of Active Share to detect closet indexing may instead create legal risk.

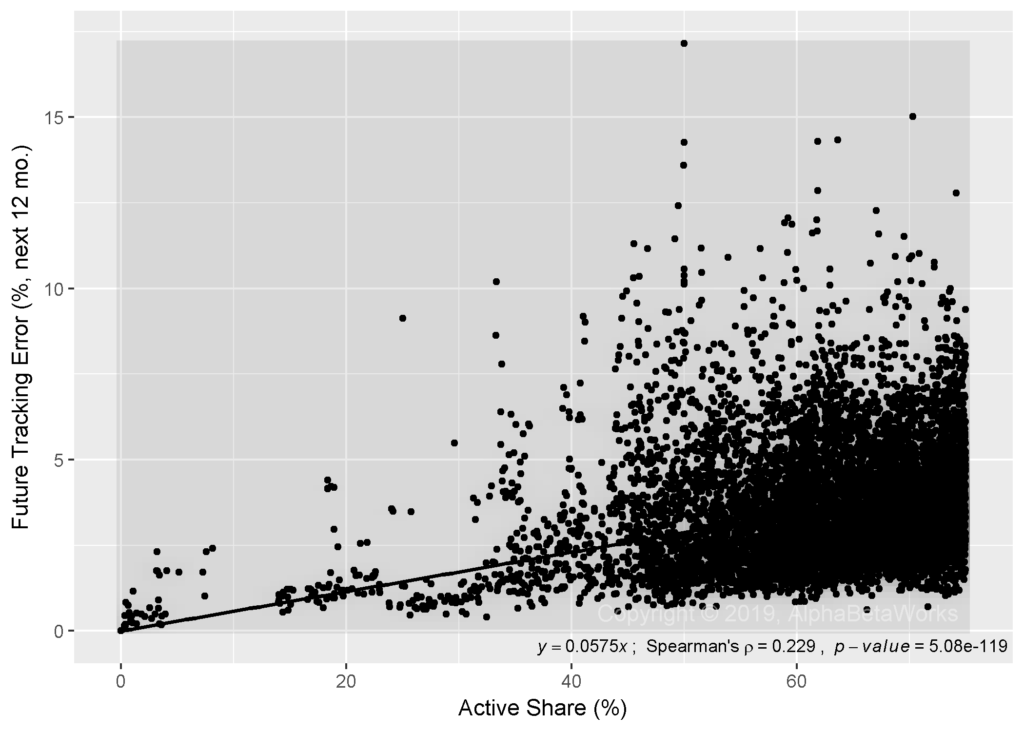

The Predictive Power of Active Share to Forecast Future Tracking Error

Although Active Share is a statistically significant metric of fund activity, it is a weak one. Active Share predicts only about 5% of the variation in tracking error across mutual funds:

Residual standard error: 1.702 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.05163, Adjusted R-squared: 0.05154

F-statistic: 544.3 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

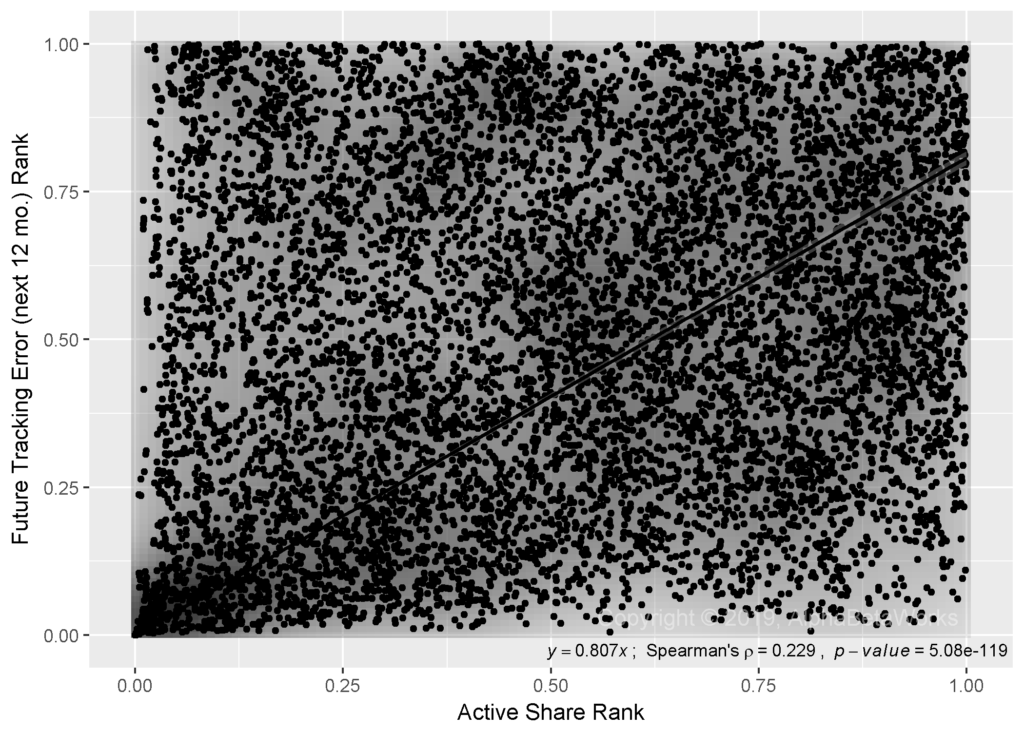

The distributions clearly suffer from heteroscedasticity, which can invalidate tests of statistical significance. To control for this, we also consider the relationship between the rankings of Active Share and future tracking errors. This alternative approach does not affect the results:

Residual standard error: 2811 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.05226, Adjusted R-squared: 0.05217

F-statistic: 551.3 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

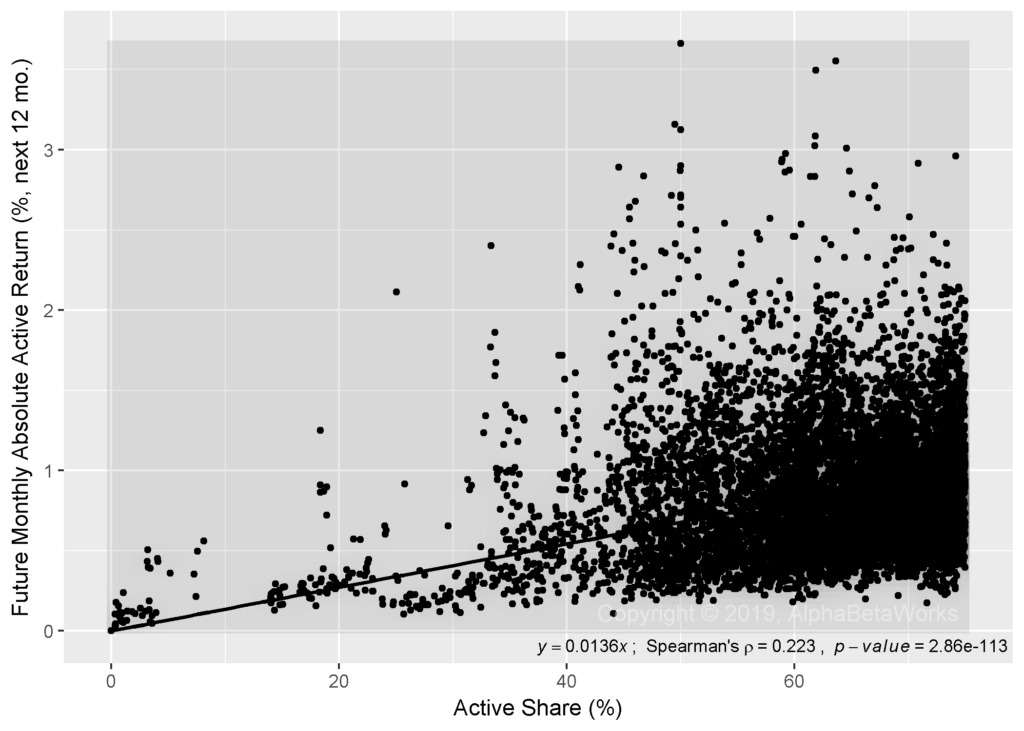

The Predictive Power of Active Share to Forecast Future Active Returns

Active Share also predicts approximately 5% of the variation in monthly absolute active returns across mutual funds:

Residual standard error: 0.3986 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.04999, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04989

F-statistic: 526.1 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

The above results make a generous assumption that all relative returns are due to active management. In fact, much relative performance is attributable to passive differences between a portfolio and a benchmark. We will illustrate this complexity in our follow-up research.

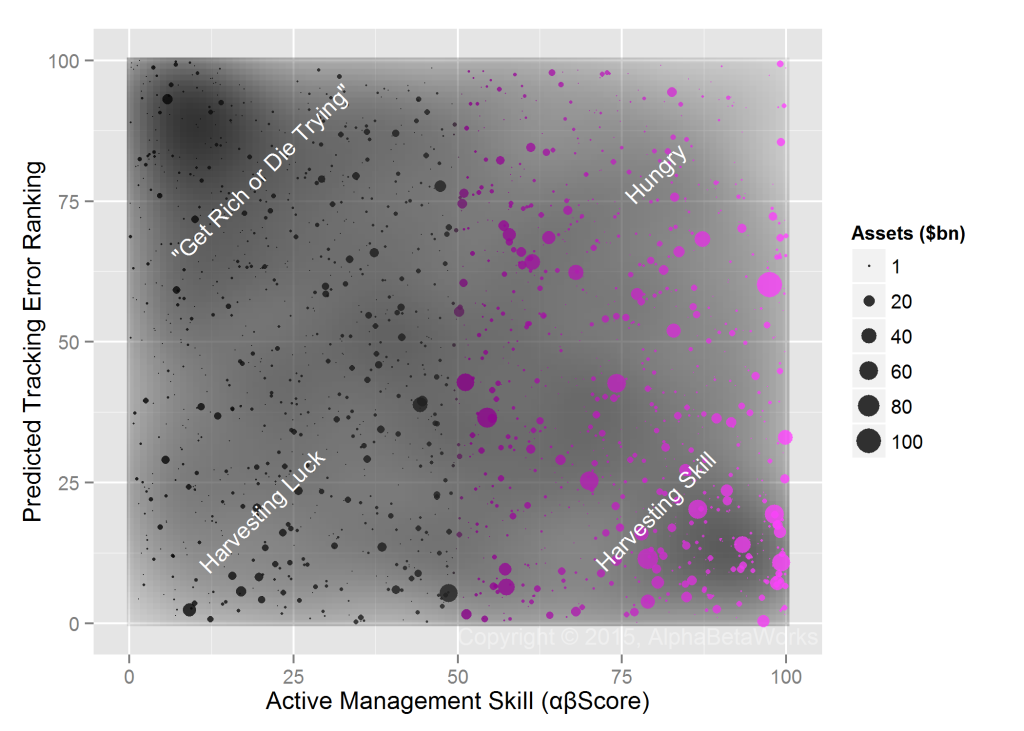

The Predictive Power of Robust Equity Risk Models

To put the predictive power of Active Share into perspective, we compare it to the predictive power of tracking error as estimated by robust and predictive equity risk models. Instead of Active Share, we use AlphaBetaWorks’ default Statistical U.S. Equity Risk Model to forecast tracking error of a fund F at date D.

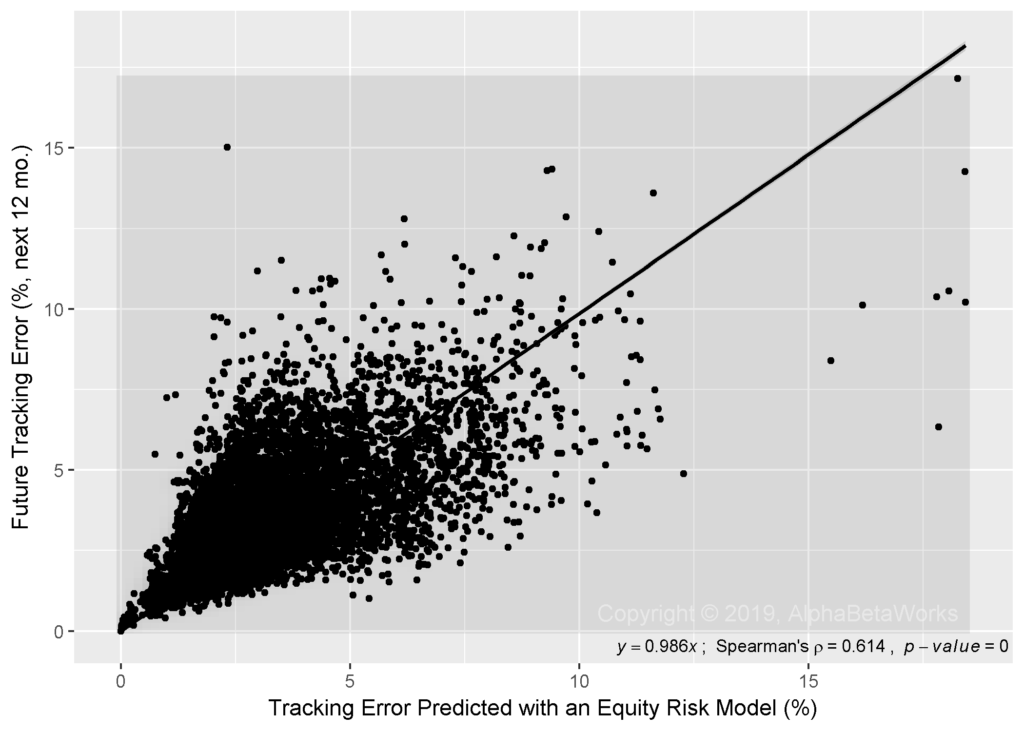

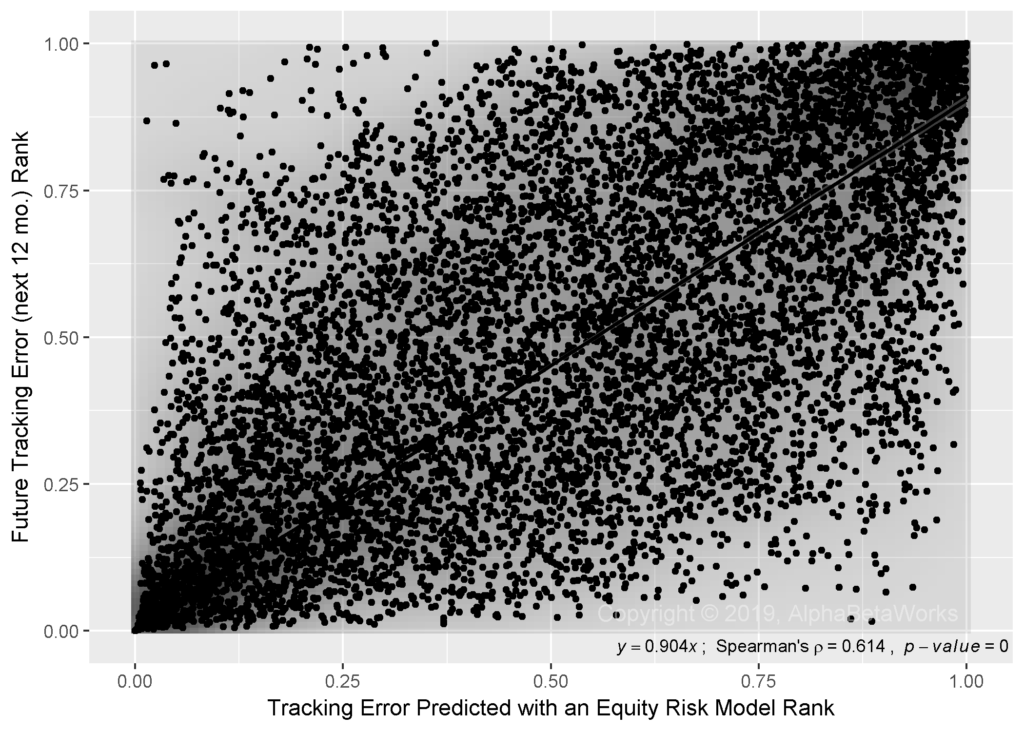

The Predictive Power of Equity Risk Models to Forecast Future Tracking Error

The equity risk model predicts approximately 38% of the variation in tracking error across mutual funds:

Residual standard error: 1.379 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.3776, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3776

F-statistic: 6067 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

As with Active Share above, heteroscedasticity does not affect the results. We see a similar relationship when we consider ranks instead of values:

Residual standard error: 2278 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.3773, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3772

F-statistic: 6058 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

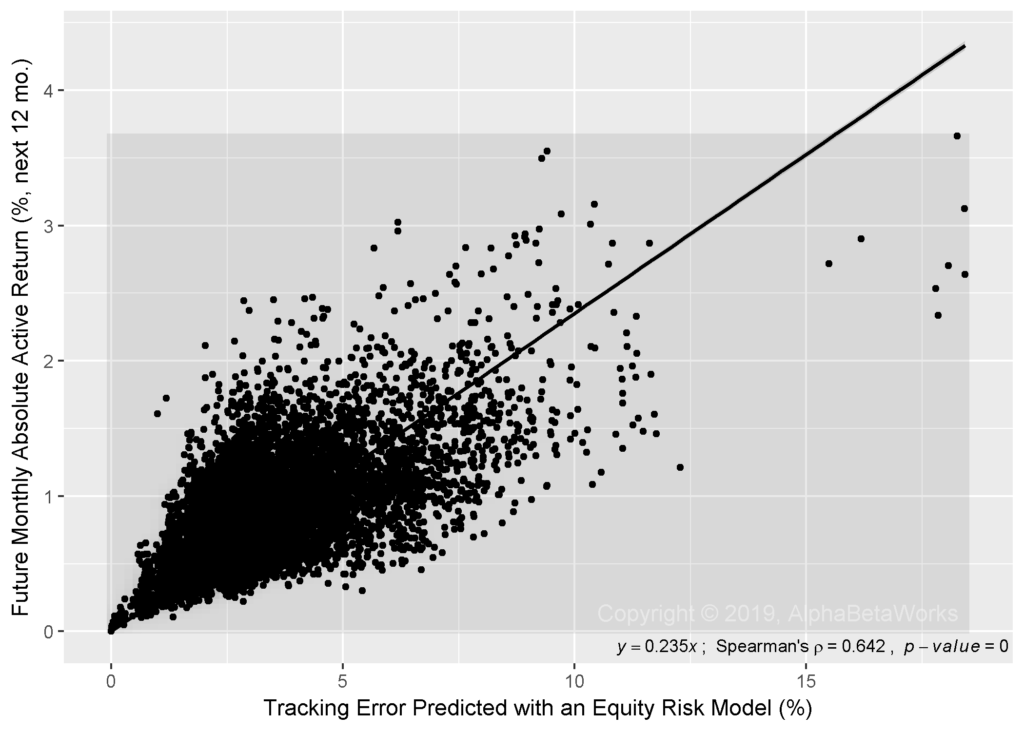

The Predictive Power of Equity Risk Models to Forecast Future Active Returns

The equity risk model predicts approximately 44% of the variation in monthly absolute active returns across mutual funds:

Residual standard error: 0.3068 on 9998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.4375, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4374

F-statistic: 7776 on 1 and 9998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Conclusions

- Active Share is a statistically significant metric of active management (there is a relationship between Active Share and how active a fund is relative to a given benchmark), but the predictive power of Active Share is very weak.

- Active Share predicts approximately 5% of the variation in tracking error and active returns across U.S. equity mutual funds.

- A robust and predictive equity risk model is roughly 7-9-times more effective than Active Share, predicting approximately 40% of the variation in tracking error and active returns across U.S. equity mutual funds.

- In the following articles, we will put the above predictive statistics into context and quantify how likely Active Share is to identify closet indexers.

The information herein is not represented or warranted to be accurate, correct, complete or timely. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Copyright © 2012-2019, AlphaBetaWorks, a division of Alpha Beta Analytics, LLC. All rights reserved. Content may not be republished without express written consent.